2017 FAA UAS Symposium attendees learn about vulnerabilities to cyber attacks

The FAA cannot tackle the issue of cybersecurity without industry, FAA’s Wes Ryan told the crowd during a cybersecurity panel at the 2017 FAA UAS (unmanned aerial system) Symposium last week. Audience members voiced concerns regarding both manned and unmanned aircraft, but the basis to any solution is that there is a need for an exchange of ideas and expertise from the aviation industry to the government.

The panel was moderated by Susan Cabler, assistant manager of the Aircraft Certification Design, Manufacturing and Airworthiness Division for the FAA’s aircraft certification service. Panelists included Ryan, manager of Programs and Procedures (Advanced Technology), for the FAA Small Airplane Directorate; Richard Morgan, director of National Airspace Security and Enterprise Operations for FAA Technical Operations Services; Tim Shaver, manager of the Aircraft Maintenance Division for the FAA Flight Standards Service; and Greg Rice, senior engineering manager for Cyber Systems at Rockwell Collins.

“We cannot, because we’re a government agency, pay what a cybersecurity expert can make out in the industry because of the criticality of the subject matter,” Ryan said. “So this has been a challenge of ours for a very long time. And the discipline changes. If we don’t have the expertise internally, we have to go seek that expertise. And that’s exactly what this session is meant to help us do; it’s an exchange.”

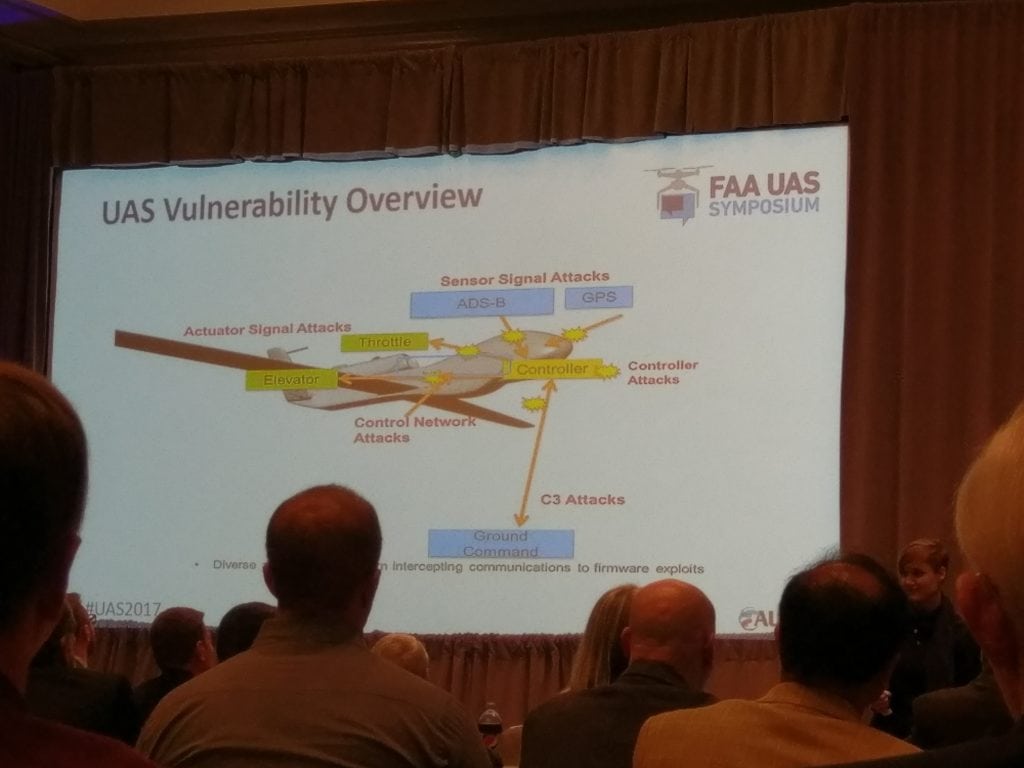

As concerned as some of the audience members were, with several questions regarding the security of ADS-B and open source software, the FAA does not have all the answers. Expertise in cybersecurity is also difficult to obtain, Ryan explained, because the technology changes so rapidly. Someone who was an expert in GPS 20 years ago, he said, is not going to be able to use that same knowledge for GPS today. FAA said it is approaching this issue with interagency, international aviation authorities and industry partnerships.

“Another avenue that we’re exploring at the FAA is how to engage the international community,” said Cabler. “[The International Civil Aviation Organization] is having a summit over in Dubai next week. Both Richard [Morgan] and I will be attending. But there’s a lot of good information that we need to share at that level. We’re hoping that ICAO can help us — not design a regulatory framework — but give us the underpinnings of a regulatory framework that we can accept globally.”

There are also lessons on improving cybersecurity practices that the FAA has been capturing from the automotive industry. Self-driving cars have already required implementation of cyber attack mitigation methods. Aviation may have a leg up in developing cybersecurity measures, considering the ever-present safety-first philosophy the industry is built on. Rice mentioned how the automotive industry did not preemptively act on cybersecurity the way the aviation community is, spurred into action by the rapid devilment of the drone industry.

“In aviation, we have a lot of safety mechanisms in place today to try to prevent those types of attacks. We alluded to some earlier, like partitioning mechanisms. That makes cyber attacks in the space very difficult,” Rice said. “But we have the opportunity right now to not react in the way that the automotive community did. We’re talking about cybersecurity at a very early UAS conference. So as we think about new features and new technologies in this space, like remote IP identification and [unmanned aerial vehicle] tracking, let’s think about how we want to assure those links, and how we want to make sure that the information being provided over those links can be assured. Let’s think about the software that’s operating onboard those UAVs, and how we can assure that that software is as free of vulnerabilities as possible.”

Once the software is developed, though, it would have to be certified, depending on implementation. This is a problem shared by the aviation industry in general, not just by drones. One audience member at the symposium posed the question of how drone operators can be sure the software they’re purchasing, like open source or otherwise, is safe and secure. Rice said he’s noticed a small push in the aviation industry for software that has been verified. He would like to see more of a push in both sectors of maintaining link integrity and mitigating cyber attack risks. The aviation industry is not known for its quick certification or acquisition processes, which is a significant hurdle when technology is changing and being developed so rapidly. But even though there are infrastructural items to sort out, industry has an opportunity to start doing that at what Rice feels is an early stage of the industry.

“We have the capability in this space to be more proactive. We’re standing at the precipice of a new community here as we start to look at some of those command and control links.,” Rice said. “We want to think about, ‘how would we do encryption…’ It doesn’t have to necessarily provide confidentiality over the links, but it should provide integrity over those links. We have the opportunity has a community to define what those standards are going to be.”