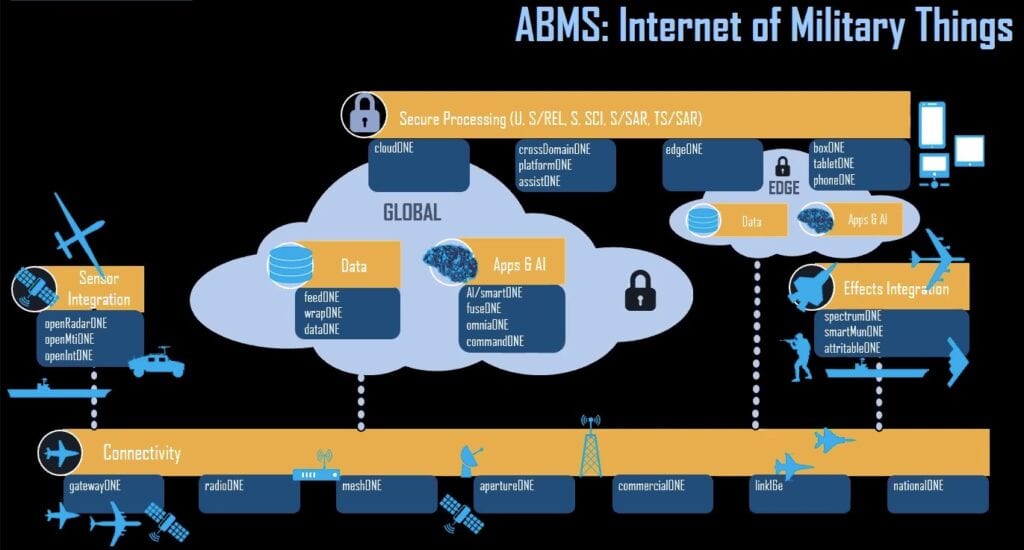

The U.S. Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System is part of the Pentagon’s broader effort to improve data integration and accessibility and enable machine-to-machine communication. (U.S. Air Force)

The U.S. military may in the next decade develop a concept of operations to employ artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)-enabled drones as a first wave in future conflicts, in order to avoid casualties and increase combat efficiency.

Efforts in this direction are underway in both the U.S. Army and Air Force, while the undersecretary of defense for intelligence and the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center are undertaking a number of initiatives, including the pioneer Project Maven and a possible follow-on. Since the spring of 2017, Project Maven has looked to develop an AI tool to process data from full-motion video (FMV) collected by unmanned aircraft and decrease the workload of intelligence analysts.

On May 20, 2017, former Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work assigned to the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team (AWCFT) under the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence the task of the automation of Processing, Exploitation, and Dissemination (PED) of tactical and mid-altitude full-motion video from drones in support of operations to defeat ISIS insurgents.

A Naval special warfare group and other U.S. Special Operations Command teams initially saw the potential of AI algorithms for shortening the targeting cycle but also found them to result in false detections and to be unable to distinguish between men, women and children readily.

Integrating data across classification levels is the biggest challenge for the effective employment of AI for U.S. military forces in the field, according to a new paper for the Modern War Institute at West Point by Tufts University Prof. Richard Shultz and United States Special Operations Commander Army Gen. Richard Clarke.

“Every step of the [data handling] process required direct human interaction,” per the paper, Big Data at War: Special Operations Forces, Project Maven, and 21st Century Warfare, which delves into the history of Project Maven. “While the process has gained some increased automation over time, the lack of a dedicated cloud-based data management infrastructure capable of quickly cutting across classification levels is the greatest roadblock to advancing AI capabilities for the warfighter.”

In the early stages of Project Maven, the project team “started out thinking they only had to focus on adopting the best algorithms, but they realized the need for a new interface system to better integrate algorithms with the users,” the study said. “They successfully turned to a leading commercial vendor who supplied an improved platform for human-machine teaming.”

Google was the prime contractor for Project Maven but dropped out in 2018 after receiving pushback from employees about the company’s tools being used for an AI drone imaging effort. News reports have said that California-based big data analytics company, Palantir Technologies, co-founded and chaired by billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel, has assumed Google’s role.

U.S. SOCOM has expanded its partnership with Project Maven and Air Force research and development personnel “to build an algorithmic capability that will blend publicly available data with classified information across the intelligence, planning and operational portfolios,” per the report. “This vision has expanded beyond Project Maven and USSOCOM, and now features prominently in DoD’s Digital Modernization Strategy.”

“Since the spring of 2018, the AWCFT and its SOF partners have endeavored to move Project Maven beyond these initial challenges to solve the PED problem and further realize the potential of AI-enabled mission command,” the report states. “Recent assessments by SOF leaders report a near-transformative effect of the human-machine interface in producing a functional common operating picture. Under the hood, the algorithms are improving as well, exhibiting greater utility and accuracy.”

JAIC has also moved forward on AI and in May awarded Booz Allen Hamilton [BAH] a task order potentially worth $800 million over five years to deliver AI-powered capabilities for use on the battlefield.

Army leaders, for their part, are interested in autonomous air launched effects, including helicopters’ deployment of jammers and decoy, ISR, and standoff weapon-equipped drones to keep U.S. military personnel out of harm’s way. The Army’s Area-I Air-Launched, Tube-Integrated, Unmanned System (ALTIUS) is to fire Rafael Advanced Defense Systems’ Spike missile, which has an advertised range of 32 km — nearly eight times that of the Lockheed Martin [LMT] AGM-114 Hellfire.

The Army also recently selected a group of companies to develop new Air Launched Effects for its future helicopter fleet that would offer the ability to autonomously or semi-autonomously deliver a range of “scalable effects to detect, locate, disrupt, decoy, and/or deliver lethal effects against threats.”

Officials said the project is aimed at delivering new drones with unique mission systems and payloads capable of penetrating adversaries Anti-Access/Area Denial environments from platforms such as the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft.

One of the biggest challenges ahead for military adoption of drones as a first wave force in future conflicts is cultural, as manned aircraft personnel feel their livelihoods threatened by unmanned systems. This may be unfounded, as such personal could see a shift — rather than elimination — of their jobs from manual, rote tasks to analytical ones.

The Army is taking the same philosophy as the Air Force in leveraging AI-enabled unmanned systems to reduce potential harm.

“If we’re going to take a big airplane with people on it into harm’s way in a future fight, we’re going to have to explain why we couldn’t do that mission differently,” said Air Force acquisition chief Will Roper. “I’ll be the first to tell you we’re not ready to pull people out of the fight, to AI everything up. R2D2 is great in the movies, but R2D2 in the real world gets really confused when an adversary is trying to mess with the data they’re ingesting to make decisions. Adversarial tactics are the death of current machine learning.”

“I think the first thing we’re going to have to do is pull people back from that leading edge of warfare where things are so lethal and uncertain, especially early in a conflict,” Roper said. “I see a huge potential to automate that, to have drones and unmanned systems take on that dangerous job. One of the most important things they’re going to do is produce data that we can use to get smarter about what that contact point of war looks like. I think that those leading edge assets, whether in the air, on the sea, or on the ground, will have to be quarterbacked by people in platforms that are standing back, ready to make the calls.”

The upcoming test of the U.S. Air Force Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) in the next few weeks is to feature collaboration among all the military services, 70 industry teams, 65 government teams, 33 platforms, and two combatant commanders, as the Air Force moves toward fielding rapidly upgradable systems and clean sheet designs featuring AI/ML.

ABMS, which the Air Force describes as the air and space “military Internet of Things,” is part of Joint All-Domain Command-and Control (JADC2), an effort to build a cross-service digital architecture for multi-domain operations, with machine-to-machine interfaces to ensure that “our personal lives are at least moderately reflected in the military that goes to war,” Roper said.

The ABMS “on ramp” tests are to be held every four months to highlight how new technologies perform, including Cloud One, Platform One, and software defined radios, and move the promising ones toward fielding within weeks through the employment of agile software. That would mark a marked change from the legacy, years-long acquisition cycles of the Cold War.

The Air Force is planning to integrate Project Maven into next month’s ABMS test, and Cloud One/Platform One will host Maven.

ABMS is the key priority for the Air Force, which has requested $3.3 billion for it over five years, including $302.3 million in fiscal 2021.

“I think we’ll eventually rename Advanced Battle Management System because it really isn’t battle anymore,” Roper said. “It started as the recap of JSTARS, as airborne battle management, and expanded into advanced battle management when we realized we’d probably have to have air and space and maybe ground components to replace that mission. But then we realized, if you actually want to be able to distribute something and have those distributed platforms be able to work together seamlessly, you’ve signed yourself up to build an Internet of Things. You’re going to need software-defined systems, cloud, containerized software so you can move it from the cloud to the edge.”

The Air Force’s intent with ABMS is to tailor data to user needs, but also to make data widely available.

“What we want to do is make sure that machine-to-machine data exchanges occur everywhere, that if any sensor sees something, that data is available to a shooter anywhere without impediments [like] human driven processes, phone calls, work chats,” Roper said.