The FAA’s first publication on air taxi operations, an evolutionary approach centered on exclusive corridors, garnered a mixed reaction from industry. (FAA NextGen)

The Federal Aviation Administration’s NextGen office recently published its V1.0 Concept of Operations for urban air mobility, developed in collaboration with NASA and industry. The document, an initial communication after discussions with industry last fall, lays the foundation for how high-volume cargo and passenger air taxis will begin to operate within the national airspace system — largely without the involvement of air traffic controllers.

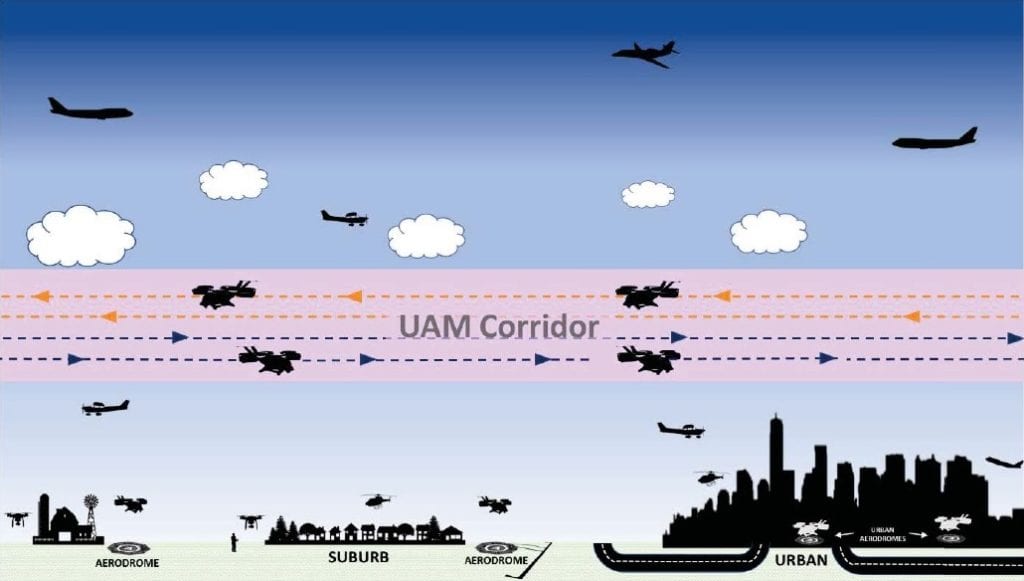

The ConOps document envisions a transition from current helicopter routes to UAM Corridors, defined and declared by the FAA but largely governed by industry and other stakeholders through a process of community-based rulemaking (CBR). In order to operate within a Corridor, aircraft will have to meet its performance requirements and restrictions, which can differ from the surrounding airspace and from Corridor to Corridor.

“Within the UAM cooperative management environment, the FAA maintains regulatory and operational authority for airspace and traffic operations,” the document states. “UAM operations are organized, coordinated, and managed by a federated set of actors through a distributed network that leverages interoperable information systems.”

The notional UAM architecture presented by the FAA. (FAA NextGen)

Air Traffic Control (ATC) will determine the availability of Corridors based on surrounding conditions and operations, but within them will not provide tactical separation services. Instead, safe operations will be collaboratively ensured by pilots-in-command (either within the vehicle or remote) and providers of UAM services (PSUs), defined in the FAA’s ConOps document as similar to UAS service suppliers within the agency’s UTM ConOps.

As rising remand and technological improvements create the need and capability for higher-tempo operations, stakeholders can use the community-based rulemaking process to accommodate increased traffic by raising various performance and operational requirements, subject to FAA approval. FAA can also change the dimensions of Corridors or establish internal ‘tracks’ to support higher-tempo operations.

Reaction to the proposed ConOps across industry has been mixed, though most experts Avionics International spoke with applauded the FAA for releasing an important starting point. Uber, likely to be a key player in commercial UAM operations, did not respond to a request for comment.

“We commend the FAA for developing this initial ConOps, and for their UAM work with NASA and industry partners,” said Ben Marcus, co-founder of AirMap, a UAS service provider and member of the FAA’s Remote ID technology cohort. “UAM corridors are an important first step in making autonomous flight a reality in our cities. We believe that as UAM adoption increases in the longer term, low-altitude airspace will become less constrained and more dynamically allocated.”

Jon Hegranes, founder and CEO of Kittyhawk, told Avionics the community approach to rulemaking illustrated that the FAA is thinking about UAM “in a new way and not trying to squeeze UAM into legacy systems,” but the proposed PSU architecture adds unnecessary complexity.

“The creation of a new PSU structure that needs to interact with the established USS framework adds unwarranted complexity,” Hegranes said. “Laying the conops of the Notional UAM Architecture diagram over the Notional UTM Architecture should have a lot more overlap and synergies whereas we have two very different diagrams.”

Christopher Cooper, director of regulatory affairs for the Aircraft Owners & Pilots Association (AOPA), told Avionics his organization supports efforts to safely add new entrants and operations into the airspace, but is concerned that the document’s emphasis on creating exclusive corridors would lock a variety of users and aircraft out of important airspace through technology and performance requirements, an approach more emblematic of separation than integration.

The ConOps briefly mentions the role of the public or local public safety organizations — as recipients of remote ID information, for example. But the document does not provide a process for local authorities and elected officials to be meaningfully involved in the location and creation of FAA-approved Corridors, noted Anna Dietrich, co-director of the Community Air Mobility Initiative (CAMI).

“The geographic determination of the aerodrome locations and the corridors themselves is a question that must have a high level of input from local authorities and the communities in which the aircraft will be operated,” Dietrich wrote in a personal blog post. “While … I support the idea that the FAA has preemption over all airspace, the document is silent on the role that local land use zoning and other tools might play in ensuring that appropriate effort be made to achieve the maximum balance of economic and community benefit, utility, adverse impact mitigation, transit integration, and social equity for these corridors.”

Dietrich also raised a number of other concerns about the document, including the lack of strong protection of the corridors from surrounding uncooperative air traffic, little discussion of vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) self-deconfliction and sequencing, and the potential for inequitable access to corridors through demand capacity balancing.

NASA is working on its own UAM concept of operations that will be published in the next few months, according to Parimal Kopardekar, director of the NASA Aeronautics Research Institute (NARI), though that document will focus on scalable operations at a greater maturity level rather than early integration.

As is the case with all “first stabs” at something entirely new, the FAA’s V1.0 UAM ConOps document leaves the careful reader with many more questions than answers, but the beginnings of a vision for UAM integration without direct ATC involvement are evident.