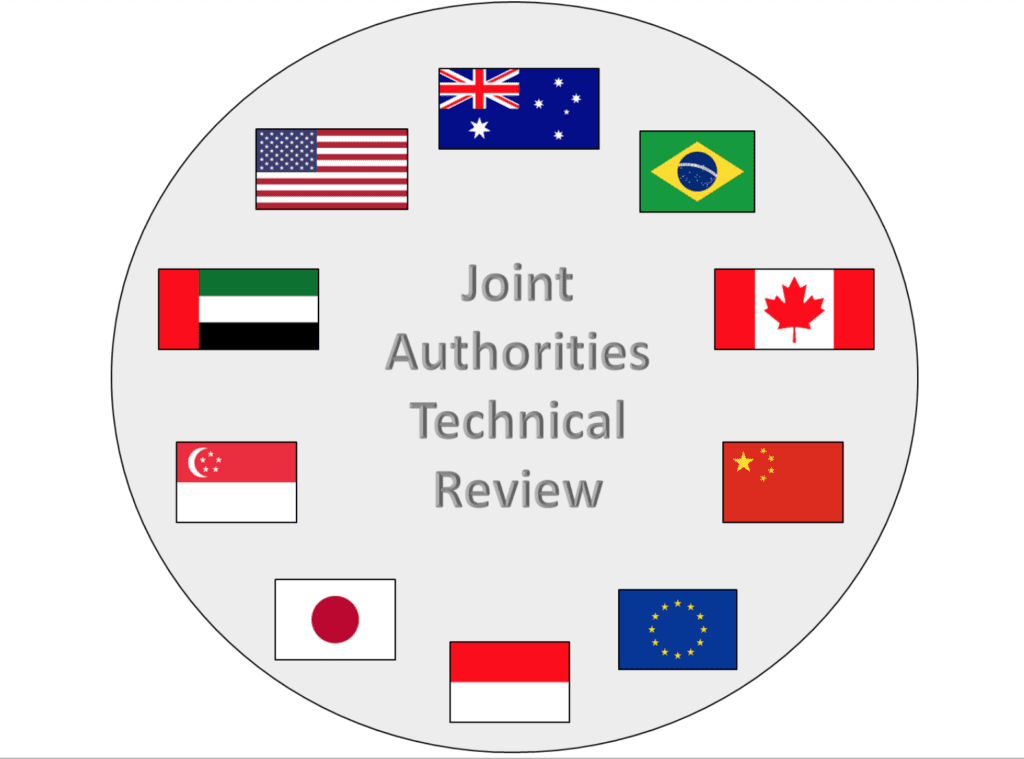

On October 11, the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR), consisting of technical representatives from the FAA, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and civil aviation authorities from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Europe, Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates submitted their observations of the 737 MAX flight control system performance and certification to the FAA.

An international team of civil aviation regulatory authorities from 10 different countries submitted a 71-page technical review of the Boeing 737 MAX flight control system to FAA Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety Ali Bahrami Friday Oct. 11. JATR’s submission comes as the global fleet of in-service MAX aircraft remains after two fatal accidents involving Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines killed a combined 346 passengers and crew.

The review includes an in-depth analysis of the certification process, considerations for human factors in pilot response to unexpected scenarios and a focus on the aircraft systems level integration and the design and performance of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS).

A total of 12 different recommendations were submitted that include the following:

- Revise and require a top-down approach evaluation from a whole aircraft system perspective for the FAA’s “Changed Product Rules (e.g., 14 CFR §§ 21.19 & 21.101) and associated guidance (e.g., Advisory Circular 21.101-1B and FAA Orders 8110.4C and 8110.48A).”

- Update certain out of date certification procedures related to state of the art designs, with a particular focus on conformity requirements for engineering simulators and devices the data and techniques used for stall demonstrations providing flight guidance systems and flight manual requirements.

- Review the identification of flight deck effects, functional hazard assessment and potential workload effects related to the 737 MAX’s flight control system, per “FAA Order 8110.4C, Type Certification, and related guidance.”

- Consider changes to the FAA oversight process involved with delegating some of the aircraft certification authority aircraft design changes between the FAA’s Organization Design Authority program and the Boeing Aviation Safety Oversight Office (BASOO), which the JATR found in some cases BASOO engineers had “limited experience and knowledge of key technical aspects of the B737 MAX program.”

- Conduct a workforce review of BASOO’s engineer staffing level and ensure that Boeing ODA engineering unit members are “working without any undue pressure when they are making decisions on behalf of the FAA.”

- Encourage applicants for type certificate design changes to include a system safety function analysis method for their aircraft performance review that is independent from the design organization and can provide impartially produced safety assessment of an aircraft’s flight control system.

- Expand the available aircraft certification resources that focus on human factors and human system integration within the aircraft certification process. JATR’s review of the certification process found that the FAA has “has very few human factors and human system integration experts on its certification staff.”

- Based on the use of SAE International’s Aerospace Recommended Practice 4754A, the FAA should consider amending Advisory Circular 20-174 to provided a better articulation of the principles ARP4754A as it relates to classifying failure conditions. AC 20-174 defines the FAA’s recognition of ARP4754A as an acceptable method for establishing a development assurance process for the certification of civil aircraft systems.

- The process of evaluating operational impact, systems integration and human performance under the responsibility of the FAA’s Aircraft Evaluation Group (AEG) needs to improve how it incorporates operational design assumptions of crew responses. JATR also recommends that FAA’s AEG gets involved in the certification process at the requirements definition phase.

- Develop a new documented process that will determine what information is featured in the airplane flight manual, flight crew operating manual and the flight crew training manual. FAA is also encouraged by JATR to review how pilots are trained to handle “mis-trim events.”

- Study the adequacy of the “policy guidance, and assumptions related to maintenance and ground handling training requirements.” JATR was limited in its ability to provide details on this recommendation due to the team’s lack of maintenance expertise.

- Review how safety risk and interim airworthiness directive action following a fatal airplane accident, while also ensuring as much sharing of post-accident safety discoveries with the international civil aviation regulatory community as possible.

An overview of the T-shape principle of basic instruments scan Boeing 737 MAX displays. A key focus within the observations and findings portion of JATR’s 737 MAX technical review was is emphasis on consideration for human factors and reactions to unexpected occurrences, such as those that occurred in the Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air accidents. Photo: Boeing.

JATR’s review included explanations and discussion of each recommendation that provided a event-driven review of the 737 MAX development assurance certification/validation reviews conducted by the FAA, EASA and Transport Canada. One of the key findings of the team of international civil aviation regulators were observations made about how test pilots react to malfunctioning flight control systems such as the MCAS versus how revenue flight operating pilots who are not expecting that type of malfunctioning that test pilots are training for, will react.

According to the review, the FAA’s guidance for flight testing during certification of transport category airplanes assumes that pilots will be able to respond to a malfunction correctly within four seconds of the occurrence of said malfunction.

JATR, in the review, writes that “in the case of the B737 MAX, it was assumed that, since MCAS activation rate is 0.27 degrees of horizontal stabilizer movement per second, during the 4 seconds that it would take a pilot to respond to an erroneous activation, the stabilizer will only move a little over 1 degree, which should not create a problem for the pilot to overcome.”

The group noted that it could not find any studies that could substantiate the guidance around recognition and reaction time.

Another major finding included as an explanation to the sixth recommendation is the discovery by JATR that Boeing did not include the use of sensors or what are described as “limits of authority” that would have provided fault toleration for the MCAS system.

Since the MCAS system was already operational on the military tanker version of the Boeing 767, the KC-46A, at the time of the development and flight testing of the MAX ,the JATR team found that Boeing engineers did not consider it to be “new or novel.”

Software on the MCAS system features the use of a “lookup table,” according to JATR, that uses high speed values in the 767 tanker configuration. However, JATR’s review says that low speed values were added to that lookup table during 737 MAX flight testing. This lead to JTAR’s determination that the evaluation of worst-case scenarios involving AOA failures and resulting hazardous flight deck effects for the introduction of MCAS was not adequate during the 737 MAX certification process.

On the same day that JATR submitted its 737 MAX flight control system technical review to the FAA, Boeing made major changes to its executive structure, that introduces a separation of the roles of chairman and chief executive officer.

Dennis A. Muilenburg will remain CEO, president and a director, while David L. Calhoun, current independent lead director, will serve as non-executive chairman moving forward. That changes to Boeing’s executive structure followed the filing of a lawsuit against Boeing by the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association, and a public speech and question and answer session by Muilenburg where the CEO said the company was targeting a return to service of the MAX in the fourth quarter of 2019.