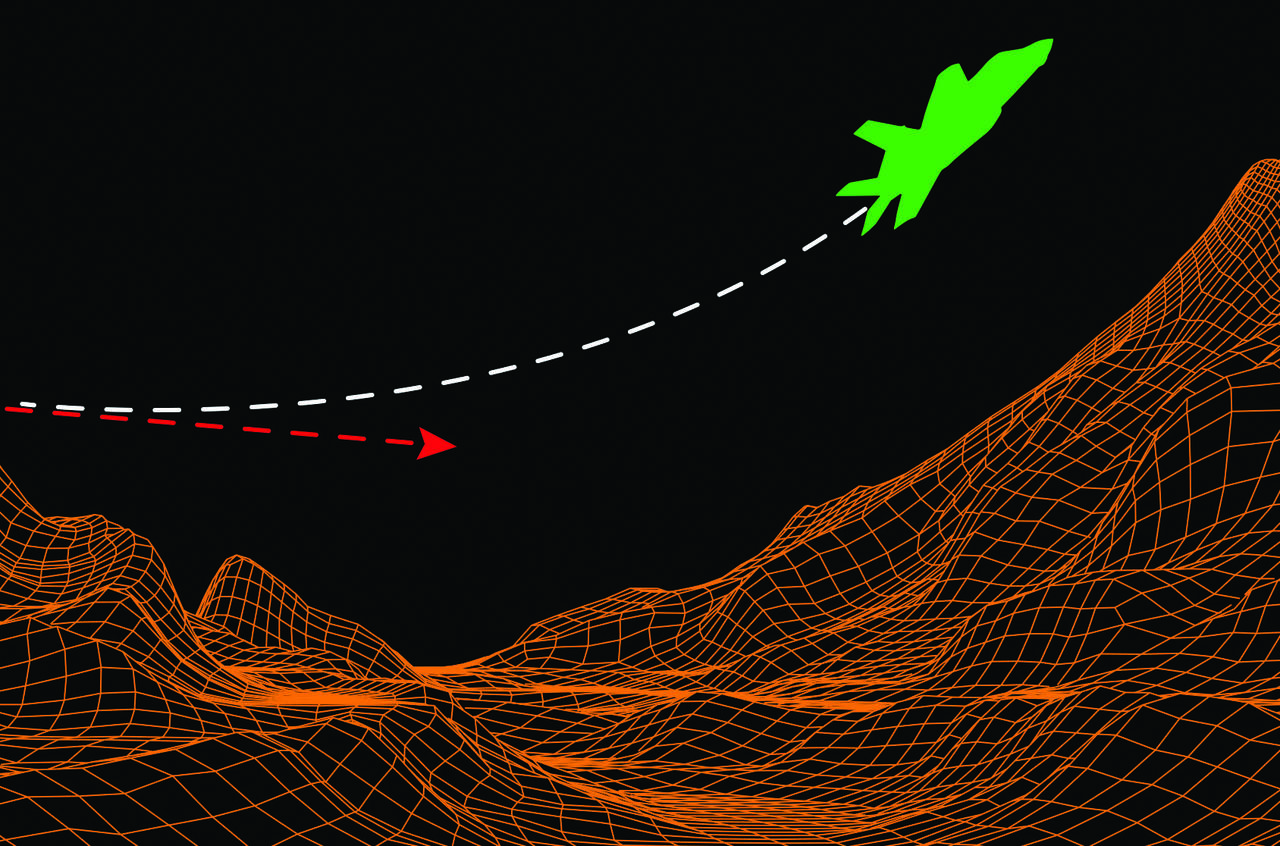

Automatic Ground-Collision Avoidance. (Lockheed Martin)

“It takes three years to build a fighter jet; it takes 26 years to build a fighter pilot. I can give you the price of an F-35, but … You can’t put a price on your sons and daughters,” said Lockheed Martin experimental test pilot Billie Flynn.

Flynn worked on one of the upcoming advancements for the F-35: an automatic ground-collision avoidance system (AGCAS). Currently on the F-16, for which Flynn also worked on it, the system does pretty much what its name says: automatically avoids the ground when necessary. To date, it has saved the lives of eight pilots (but only seven jets).

More specifically, the AGCAS uses GPS, terrain data and spatial awareness to recognize when the jet is heading toward the ground or a mountain, and if it gets to the specifically calibrated point at which it is likely too late for a pilot to react to that fact, the system intervenes and pulls the jet up on its own before returning control to the pilot.

Flynn worked on the AGCAS system along with Air Force Research Lab engineers at what is now the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center. He said they studied decades of flight data and it’s extremely rare that pilots crash simply because they’re flying too close to the ground.

“Pilots get disoriented in bad weather,” Flynn said. “They suffer spatial disorientation because they are moving aggressively at night. They get mixed up sometimes doing tasks in the cockpit and lose perspective of exactly where they’re at.

If a pilot is disoriented or momentarily unconscious, the alerts won’t help. That’s why the system is needed. It gets them out of harm’s way so they can get their bearings and take back over.

“When we sense that we’re within 1.5 seconds of hitting the ground, we can’t stand it anymore,” Flynn said. “This system is so robust that it’ll take control long after you and I, the human, would want to be pulling away from the ground if we were paying attention. It’s so precise that it will miss the ground essentially every single time. And that means that it won’t take over early from the pilot — whatever task we’re doing we will be allowed to do — but if we were way too close to (hitting) the ground, it would take control and save us.”

That’s why Flynn is now helping move the system from the F-16 to the F-35 five years ahead of schedule, for 2019 instead of 2024. And he says the applicability doesn’t stop there.

“This technology is so interesting that it’s going to end up in corporate jets,” Flynn said. “It’s going to end up in private airplanes that people fly, and it’s going to end up in commercial airplanes that you and I load onto every single week. … At some point, you’re never again going to hear about airplanes crashing into the ground, into swamps, into mountains.”

Flynn said he expects it to require commercial pressure for airlines and OEMs to decide to make the move as industry moves relatively slowly. Once the decision is made, though, it won’t take long, thanks to the sophistication of technologies such as GPS.

“A bunch of technologies came together, and that’s why it became so easy for us to develop our system in two years on the F-16,” he said. “So, do I think it’s hard to develop a system for an airplane like a 737 or an Airbus airplane or any flying vehicle? The answer is no.”

One of the things that has expedited AGCAS’s move from the F-16 to the F-35 so much is the high quality of F-35 simulators, according to Flynn. But that doesn’t mean no actual testing is required. And that’s a tough prospect because you don’t want to send pilots spiraling at the ground in a fighter jet too often hoping the jet pulls them out. The solution is to trick the system.

Normally, the AGCAS activates at 2,300 feet. For testing, Lockheed adds 10,000 more to that floor, so the F-35 thinks it is close to the ground when it gets to 12,300 feet and pulls up. That way, testers can make sure it recognizes altitude and reacts appropriately without putting a test pilot in a situation where the AGCAS is the only thing preventing him from crashing.

Beyond the delicate balance between safety and not wresting control away from a pilot unnecessarily, another concern is electronic warfare. If a system can take over piloting the plane, is it exposing the jet to danger from hacking? Not according to Flynn.

“That has never been an issue with this system,” Flynn said. “The way we’ve always worked is, it defaults off. So, it’s never going to fly you up. … Instead of someone taking control of an auto-driving car, we just return the control to the driver is the equivalent analogy.”

A so-called “nuisance fly-up” is a problem with the system that pulls the aircraft up unexpectedly.

“We have spent years stripping out the potential of any nuisance issues with the flight controls and how the aircraft behaves,” Flynn said, confident that there will be no surprises when flying alone. “We are remarkably confident that we aren’t going to have anything surprise us when we fly alone.”

Lockheed still needs to do live testing with the AGCAS in the F-35 before implementation. Flynn is confident, though. And once that is completed, the process is quick.

“Once we’re happy, it goes into all the jets as fast as possible. It’s a software drop. It’s like updating your iOS.”

This story is part of our expansive F-35 coverage. You can also learn about the fighter’s helmet-mounted display system, data fusion and information sharing, electronically scanned array radar and where the program stands heading into the future.