Global Avionics Round-Up from Aircraft Value News (AVN)

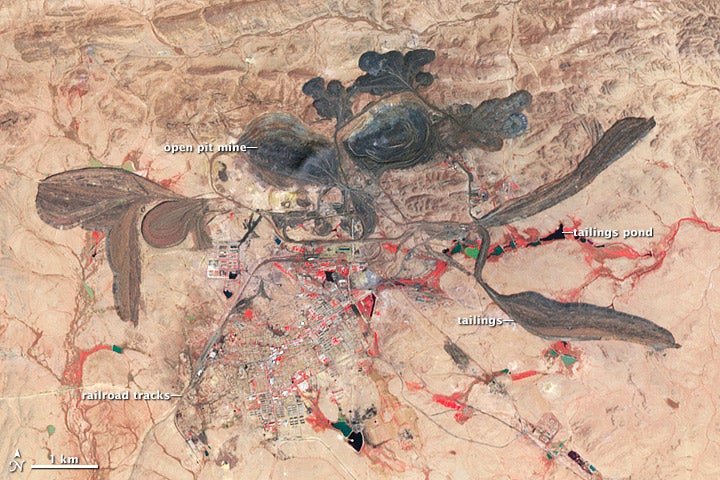

The Bayan Obo mining district in Inner Mongolia, China. The mines of the region have the largest known deposits of rare earth elements. (Image: NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using data from the NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team)

From the mine to the magnet, the value chain of avionics hardware passes through one of the lesser‑appreciated links: rare earth elements. These elements power the permanent magnets, sensors and high‑performance components inside modern avionics systems.

When China tightens its grip on rare earth exports, avionics makers feel the ripple effects, and aircraft asset managers adjust residual values and lease assumptions.

Why do rare earths matter for avionics? These elements—dysprosium, yttrium, terbium, samarium, and others—are integral to high‑performance magnets and aerospace‑grade sensors that underpin navigation, radar, engine‑control and surveillance avionics.

China dominates not just mining but refining and magnets manufacturing. By restricting access to these minerals, China holds a “stranglehold” over inputs into systems crucial to modern aircraft and defense.

China this year intensified controls over rare earths. In April, Beijing imposed export restrictions on seven heavy rare earths and rare‑earth magnets; in October, it added licensing requirements and end‑use tests targeting semiconductors and dual‑use industries. While much commentary focused on electric vehicles, the aviation/avionics sector is suffering huge implications.

What it Means in the Cockpit

An avionics supplier may rely on a magnet vendor for actuator or servo systems or need rare‑earth‑based materials for inertial sensors or radar arrays.

A delay or cost‑surge in the inputs means higher bill‑of‑materials, slower certification cycles and potential supply constraints. The new export controls could substantially impede efforts to diversify rare‑earth supply chains and ramp-up manufacturing.

Supplier risk translates into fewer upgrade options, longer lead‑times and increased cost‑capex, which in turn means operators must consider that avionics upgrades now carry higher risk and cost premiums.

From the aircraft leasing/valuation side, the implications are subtle but real. If future avionics refreshes are at risk of delay or cost‑shock, the lessor will discount the residual value of aircraft whose avionics may become “hard to support” or expensive to maintain.

For example, imagine a mid‑life airliner whose avionics upgrade plan depends on a magnet‑subsystem whose lead time has doubled; the lessee may balk at committing to another long lease, or demand a rent concession to cover the risk of downtime. That reduces lease rate and pushes residual value lower.

Also, planning horizons lengthen. OEMs that once confidently promised “cockpit upgrade available in three years” now must factor in supply‑chain risk. Investment in avionics becomes more cautious, and that means slower rollout of next‑gen systems in some fleets. Slower rollout in turn defers the expected value uplift of upgraded aircraft. For lessors, this means the “upgrade premium” is postponed or perhaps reduced.

China’s dominance of magnets and rare‑earth processing is a wake‑up call for the global aviation industry. Supply chain disruption risk suppresses the comparative advantage in rare‑earth‑dependent industries, meaning OEMs must carry additional contingency cost.

For the operator and lessor community this means a few concrete changes:

- When considering an aircraft mid‑life, examine not just the avionics version but the supply‑chain exposure of future upgrade path. If the avionics system vendor sources key materials from risk‑jurisdiction countries (China heavy), that may mean higher risk and lower value.

- Lease‑rate modelling must include contingency for avionics lead‑time and support risk. If the probability of an avionics refresh slipping or costing about 20% more increases, the lessor will reduce rate accordingly.

- Residual value forecasts should include a “supply‑chain shock” discount for avionics‑heavy fleets, especially corporate/business jets or freighters where avionics upgrades are a major part of value retention.

China’s rare earth clamp‑down isn’t just a geopolitical headline; it’s a structural risk for avionics development, hardware supply, upgrade cycles and ultimately aircraft values. Whether you’re a business‑jet operator planning a cockpit upgrade or a lessor writing a 10‑year lease, the new mineral dynamics belong in your asset‑risk equation.

The article first appeared in Aircraft Value News.

John Persinos is the editor-in-chief of Aircraft Value News.