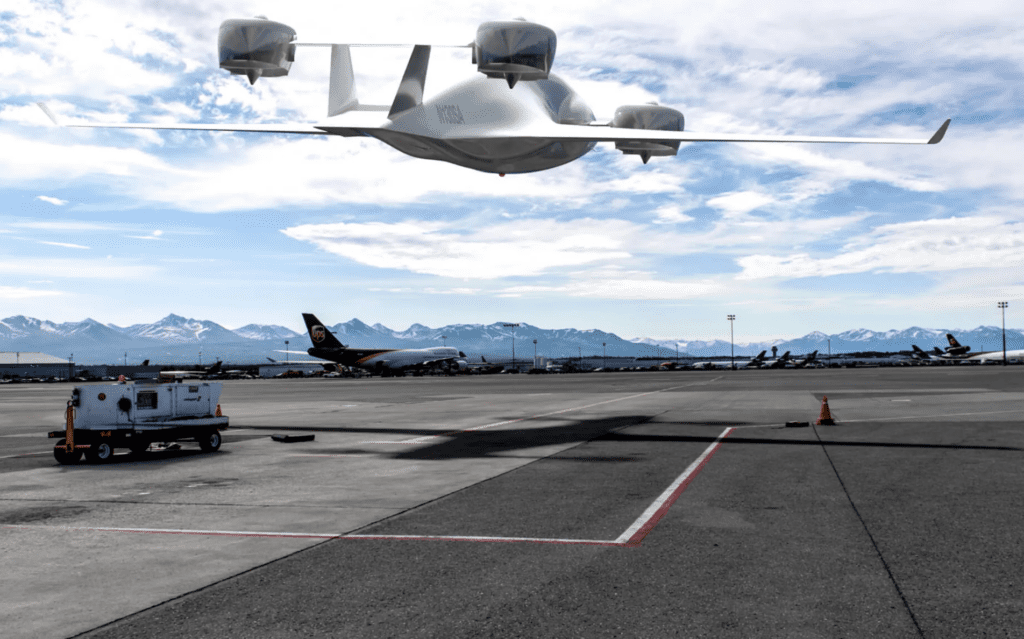

During its first hover flight, Sabrewing’s Rhaegal cargo UAV carried an 829-pound payload. (Photo: Sabrewing)

Sabrewing Aircraft Company, based in California, recently announced the successful completion of its cargo drone prototype’s first hover flight with an 829-pound payload. According to the company, this set a new world record for a commercial vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) cargo drone.

The company has a $3.2 billion order book so far, including purchase orders for 28 aircraft along with 102 firm orders and letters of intent for more than 400 aircraft. Deliveries of the first 28 aircraft are expected to start by December 2023. Sabrewing has also been awarded contracts by the U.S. Air Force to study autonomous cargo delivery.

The aircraft, called the Rhaegal, is an autonomous UAV (uncrewed aerial vehicle) that utilizes a turbo-electric drivetrain, based on the Ariel 2E motor from Safran Helicopter Engines. It can use up to 50% sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF. Along with Safran, Leonardo Aerospace, Toray, Garmin, and Attollo Engineering are some of the companies that developed the Rhaegal in partnership with Sabrewing’s team.

The prototype aircraft, the Rhaegal “Alpha,” was unveiled in April 2020. At the time, the company had already received a $3.25 million Phase II SBIR contract from the Air Force. This funding was used for research and development related to the aircraft’s navigation and detect-and-avoid systems.

The Rhaegal “Bravo” is the production aircraft which will be targeting first, middle, and last-mile cargo delivery. Other missions include firefighting, search and rescue, medical deliveries, and disaster relief, according to Sabrewing.

Ed De Reyes, CEO And co-founder of Sabrewing (Photo: Sabrewing)

Sabrewing was founded in 2016 by Ed De Reyes, chairman and CEO, and Oliver Garrow, Chief Technology Officer (CTO). Check out our question-and-answer session with De Reyes below.

Avionics: Following the first hover flight with the prototype aircraft, what’s next for Sabrewing’s team?

De Reyes: We needed to differentiate ourselves from the other cargo aircraft doing vertical flight, so we decided to take off with a payload on our first flight. We put water containers on board to get to the 829-pound payload. We could easily put two to three times more weight onboard the aircraft. Once we’ve done that, we’ll fly a series of conventional flights.

We’re going to continue to fly higher altitudes in our hover flights and continue to add weight. Eventually, we will do a transition flight with our full-scale production aircraft. We’ve done all of these already with our scale model and it performed well without any issues.

“Leonardo provides everything from TCAS to ADS-B, transponders, radio altimeters, and the flight control computer,” says Ed De Reyes, CEO of Sabrewing. (Photo: Sabrewing)

Avionics: What is your background in aviation?

De Reyes: I’m a retired Air Force veteran. After coming off of active duty and going into the reserves, I started working for companies like McDonnell Douglas, Boeing, Lockheed, et cetera. Most recently, I was with Northrop Grumman for 12 years and was able to work with several of their drone programs. I started a charter airline company doing mostly air cargo, but retired from that in 2017. That’s where I learned what it takes to run an air cargo company.

I started to look at different aircraft and their capabilities, such as electric aircraft. We came up with this aircraft after six years of design, talking to customers, talking to the people that would be utilizing this. We’re strictly an aircraft manufacturer—not a drone-as-a-service, because we aren’t competing for cargo work with our customers.

Avionics: Could you share details about Sabrewing’s contracts with the U.S. Air Force?

De Reyes: Part of it is looking at how this aircraft will be capable of delivering cargo to a remote area, including the battlefield, without putting human life at risk to get there. The point of the demonstration is to show that we could launch the aircraft with a simulated payload and to demonstrate how the aircraft would fly in a GPS-denied environment and land precisely without GPS, because it could be denied in a battlefield.

We also look at casualty evacuation. For those with casualties that need to be relocated via helicopter from a battlefield, the distance traveled is typically about 50 miles. For a major casualty, there is something called the “golden hour” where if you can get them to the hospital within an hour, their chances of survival are very high.

With helicopters, even if they’re flying 100 miles an hour, they have a very short period of time to get people onboard. Our aircraft easily flies at 230 miles per hour. We can get there in as little as 15 minutes, load them, and take them directly to the hospital within an hour. Those are the capabilities that we hope to be demonstrating here very shortly.

Sabrewing’s Rhaegal “Bravo,” the production aircraft, is an autonomous cargo UAV capable of vertical and conventional take-offs and landings. (Photo: Sabrewing)

Avionics: Do you expect any challenges in the certification process, either with the FAA or EASA?

De Reyes: There are challenges with all kinds of aircraft. I’ve been in this business for 45 years, and you kind of roll with the punches. We’ve been lucky. We have a good team on board with a lot of aircraft certification experience with all sorts of regulatory agencies throughout the world. We knew early on that we had to coordinate with those regulatory agencies in order to start down the path that we needed to be on.

The FAA is having some challenges with personnel, but we were the first company to reach an agreement on the basis of certification with the FAA back in October of 2019. We still have to do the TIA, or Type Inspection Authorization. We’re far enough along in that process, we should be good to go. We are not demonstrating maneuvers on the aircraft just yet.

Avionics: What progress has been made towards certification with the FAA?

De Reyes: We’ll continue to do flights on our half-size demonstrator aircraft that was created as a flying testbed. We have avionics we can go out and test: things like the detect and avoid system, transition system, a lot of the flight control computer, and a lot of the control logic that’s in there. We actually have an off-the-shelf flight computer and we modify the software specifically for our aircraft.

We’re currently in the process of working to produce our full-sized aircraft. We’re continuing to produce the first production prototype. In the meantime, we’ve gotten a lot of inquiries by various companies about possibly buying the half-size aircraft. There is a possibility that we could go into production with that aircraft as well.

Avionics: Could you discuss the selection of the avionics systems, navigation systems, and other components that will be integrated into the aircraft?

De Reyes: We use all Leonardo avionics with the exception of the radar that sits in the nose—the radar is from Garmin. The detect-and-avoid is our box, so to speak. Leonardo provides everything from TCAS to ADS-B, transponders, radio altimeters, and the flight control computer. Even our ground station is from Leonardo.

We talked with dozens of other companies that had various forms of controls for UAVs. The only one that really had a complete package for us was Leonardo. On top of that, the flight control computer we use is basically the same one in the AW609—the only flight control computer in production that is capable of safe transition from hover to climb to cruise, and descending to hover. They do that almost every day; it was a no-brainer for us. It’s an off-the-shelf unit for them.

The only thing we’re really going to have to have any involvement with for the TSO portion is our detect-and avoid system’s sensor interface computer. Everything that goes into it, including the DAA radar, all those are TSO’d. We’ll only need a box on our sensor interface computer, which is very manageable. Almost every component onboard the aircraft is off-the-shelf, almost every component, from motors to turbines to avionics.

Avionics: Why was a turbo-electric drivetrain selected for the Rhaegal aircraft?

De Reyes: I did a lot of research into batteries for electric aircraft as a consultant. None of the batteries that were available could give us the kind of range we need. Our range is 1,000 nautical miles. In a typical cargo operation, we would load the aircraft with as much cargo as possible and maximum fuel with reserves to get to the next airport. The problem is that the cheapest fuel is at the home base. When dropping off cargo at other airports throughout the day, the operator isn’t as in control of the profit margin.

With our aircraft, you can fuel up in the morning, load up with the maximum amount of cargo, transport the cargo to various destinations, and at the end of the day fill up the aircraft again with inexpensive fuel at your home base. This offers solid control of your profit margin, and customers really like that.

The batteries don’t yet have the range we needed. The only option was to not carry batteries, which was a good move—by not carrying that additional weight, we could increase the total payload capacity. Turbines have an excellent power-to-weight ratio, and that was perfect for us.