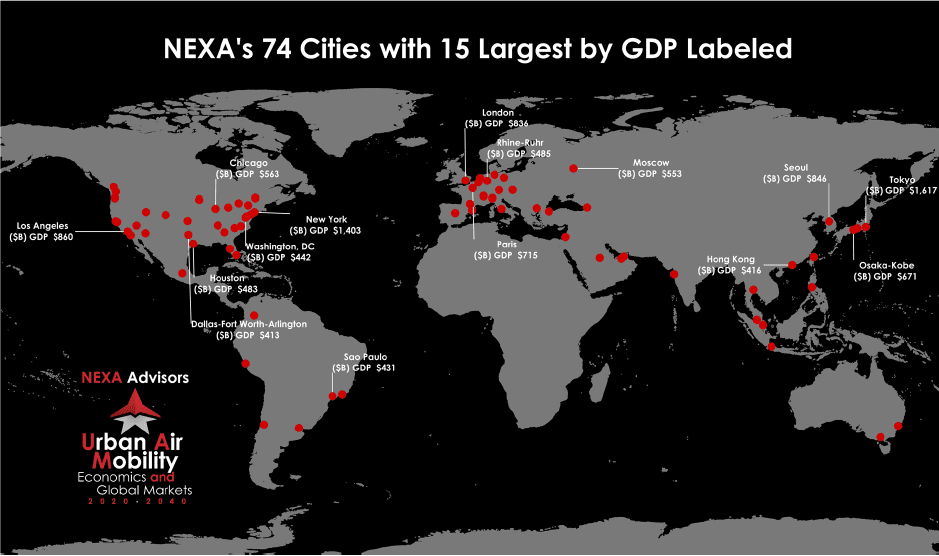

A map of the 74 cities Nexa Advisors chose to examine for their 2020-2040 urban air mobility study. (Nexa Advisors)

A global study on the economics and market for urban air mobility was released by Nexa Advisors, an aerospace advisory and investment firm.

The study provides an in-depth look at 74 cities believed capable of supporting a profitable UAM ecosystem — ranging from Tokyo to Plovdiv, Bulgaria — the firm concludes that between 2020-40 there is a direct value of $318 billion to be captured. That figure includes about $244 billion in operator revenue, $32 billion in operating costs associated with infrastructure and airspace management, and $41 billion in eVTOL vehicle sales. All figures are presented in today’s U.S. currency.

The study does not include some market segments, such as cities outside the 74 chosen, military applications and recreational or tourist uses of eVTOLs. “If analyzed and counted in, these segments could easily double or triple our forecasts,” write the authors.

In the near-term, Nexa expects eVTOL vehicles to perform the shorter-range missions in the light vertical lift market, including charter helicopter flights and emergency medical transport, using existing infrastructure in cities such as Vancouver and Sao Paulo that currently have active fleets of rotorcraft. New eVTOL designs promise to lower operator costs, improve rider convenience and mitigate public concerns around noise pollution, which the study’s authors believe will allow existing operators to expand their operations and profit margins.

“There is no doubt that helicopter operators are going to be substantial beneficiaries if this market takes off,” Michael Dyment, founder and managing partner of Nexa Advisors, told Avionics. “We have not talked to a helicopter operator not willing to put down a couple million dollars for an electric vehicle. Helicopter operators are dying to adopt this technology so they can finally make good money.”

The study is broken into four “phases,” five- or six-year increments beginning at 2020-24 and ending at 2035-40. Even in the first phase, the study projects ridership demand close to 136 million passengers — encompassing airport shuttle, on-demand air taxi, corporate campus and regional uses of eVTOLs — and creating revenues of at least $48 billion, according to the report’s authors.

Passenger demand growth over time, as modeled by Nexa. (Nexa Advisors)

“A key assumption that we’ve made is that at least some electric vehicles will be ready next year,” Dyment explained, adding that the study “may have been a little too aggressive for the first couple of years … as the forecasts go out a little longer, they get more reliable.” Dyment added that he sees “volume but not mass production” beginning in the next five years.

Some other analysts don’t foresee this level of growth in existing sectors, currently served by light helicopters, simply through the addition of eVTOLs.

“The closest analog we now have is light vertical lift — light pistons and light single turbines — and the market for that is $350 million or so per year … really not much to start with,” Richard Aboulafia, vice president of the Teal Group, said recently on Aviation Week’s podcast. “There’s all kinds of potential for market stimulation on the basis of technology. That’s very exciting. But if it’s a remarkable, precedent-setting, path-breaking 5X stimulant, you’re still left with a sub-$2 billion market that doesn’t justify the massive investment that’s being considered for it.”

“I could be wrong, and it could be that when people throw around the terms ‘flying taxis’ and ‘flying cars’ that they really are intending to tap into the broader ground transport market to replace these foolish pedestrians and cabs … and maybe there’s a way to do that,” Aboulafia continued. “But I just don’t see that happening, and if it doesn’t happen, you’re left with the vertical lift market and that’s pretty small.”

The Nexa study highlights areas of the broader aviation market where eVTOLs may find opportunity, including the $100 billion annual business aviation market and short inter-regional travel markets that airlines currently do not serve, the latter of which hybrid vehicles would be well-positioned to capture as battery density doesn’t yet allow for longer all-electric flights.

But the real cash-in for the billions being invested in eVTOL development isn’t expected to materialize in the next few years as an expansion of currently-served rotorcraft markets. About three quarters of the expected value of the UAM market, according to Dyment, lies toward the end of the time period, when operations have passed what he calls the “Inflection Point” — a Singularity-like reference to the point where automation takes a front seat, costs rapidly drop and large-volume urban air transport becomes a reality. Dyment believes this Inflection Point is eight to twelve years away.

“The full potential of UAM will be achievable only with higher levels of automation of eVTOL flight, dynamic airspace access through geofencing, UATM oversight, sense‐and‐avoid surveillance and vehicle interoperability,” the report states. “It is not difficult to visualize that cockpit automation will be necessary to improve the safety of flight, and drive costs – and ticket prices – down.”

Demand and ticket price over time, as modeled by Nexa. This averages both elastic and inelastic missions, globally. (Nexa Advisors)

The study forecasts that ticket prices, initially averaging at about $400 globally and across mission sets, will fall below $150 toward the end of the time period. These figures, however, include inelastic missions such as emergency medical transport; when removed from the average, Dyment said he foresees ticket prices for core UAM missions reaching about $100 by 2040.

However, the question remains whether the brand-new market UAM hopes to create — the dream of on-demand urban air taxis as a viable option, more cost-competitive with other means of urban transport than traditional helicopters — will materialize, creating the demand necessary to offset the tens of billions in up-front infrastructure costs necessary for the industry to exist.

“The more I cover this, the more and more concerned I become that this is just another low-volume aerospace market,” said Aviation Week reporter Graham Warwick on the same podcast.

“It’s no longer a technical issue,” Warwick said. “It’s no longer even a regulatory issue. It’s a political and a social issue. Can you actually get people to ride into these things, cities to allow people to ride in these things, and then can you get the price down to the point where it becomes…a level of public transport that people don’t point at it every time it flies over your head and say, ‘Rich people fly that, and I don’t like it, so I don’t want it here.’ Until we get the social barriers removed, the political barriers removed, I don’t see the market shifting beyond a little bit bigger than the light helicopter market today and that worries me.”

Michael Blades, vice president for aerospace, defense and security at Frost & Sullivan, doesn’t see the political and social issues as insurmountable, but says his firm has not arrived at a similar timeline or revenue figures in researching UAM.

“Amazon told us in December 2013, nearly 6 years ago now, that we would have drones delivering packages to our doorstep within 4-5 years. That hasn’t happened,” Blades wrote to Avionics. “Technology, regulatory, and procedural restraints still exist — and this is about delivering a five-pound package. We still haven’t figured out how to safely deliver a small package to consumers consistently via drone, but we are to believe that in a few short years all-electric, automated air taxis will be transporting passengers in the millions?

“In looking at the current state of technology, regulatory frameworks, and public acceptance it is difficult to see a pathway to the numbers the Nexa report arrives at,” Blades added. “While technology, regulations, and public sentiment will allow automated air taxis, eventually, we believe it will be much further to the right, and in fewer numbers than many of the overly bullish reports would have us believe.”

| Want more eVTOL and air taxi news? Sign up for our brand new e-letter, “The Skyport,” where every other week you’ll find the most important analysis and insider scoops from the urban air mobility world. |

Dyment also said he recognizes that there are existential risks to the emergence of a large-scale UAM industry — including noise and public perception — but he is convinced the value proposition is there and the acoustic problems are being solved. His team’s analysis also arrives at a very different view of the quantity of operations necessary to sustain a profitable market; unlike Uber’s vision, with upwards of 500 operations taking place per hour from massive megaports, Dyment said “the most we get to is about 11 operations per hour for a node.”

“We could never get there with our study,” Dyment explained. “We’ve been skeptical about the sort of density, the sky-packing, that Uber presents as a fundamental element of its business plan. We don’t need that, and the industry doesn’t need it … you don’t need to have that sort of [volume]. Plus, what city would want that? What city would want you to look up in the sky and see 10-15 of these vehicles at any given time, flying above you or within earshot?”

Uber’s director of aviation engineering, Mark Moore, does believe demand will justify a higher tempo of operations in more central city areas. “Clearly, there will be different sizes and capacities of Skyports for Urban Aviation depending on the passenger trip density at specific locations,” Moore wrote in an emailed statement. “There will be many distributed smaller Skyports which can accommodate 1-4 aircraft at a time, with larger Skyports being able to handle 8-16 aircraft at a time … The initial operations in 2023 will have fewer vehicles and flights as service is initiated, and a number such as 11 trips per hour makes sense for a smaller Skyport. However, as an early city evolves from having the first handful of aircraft in 2023 the number of flights needs to increase to achieve favorable amortization of the infrastructure costs, with operations increasing from 1 every 5 minutes to a tempo of about 1 aircraft per minute.”

“Our joint simulations with NASA indicate this is a reasonable pace for airspace control,” Moore added. “Our demand simulations also indicate that most urban Skyports will be positioned where substantial daily trip demand exists, and that the deamnd would significantly exceed a total of 11 flights/hour * 4 passengers/flight * 16 hours/day = 704 passengers/day/Skyport. Uber’s objective is to achieve a scaled transportation solution that can provide meaningful throughput.”

It may take decades for a clear answer to emerge. In the meantime, however, Nexa Advisors’ report breaks down the $32 billion in necessary infrastructure investment — in both vertiports and airspace management systems — into five phases of expansion, providing an exhaustive look at over 4,200 existing heliports in the 74 cities studied and ArcGIS data layers to help identify areas for fruitful investment.

Without the upfront capital investments necessary to expand beyond the current scale of operations, urban air mobility may never take off, despite the monumental technological and regulatory achievements rapidly falling into place. The city of Plovdiv for example, cannot support UAM with its current number of heliports — zero.