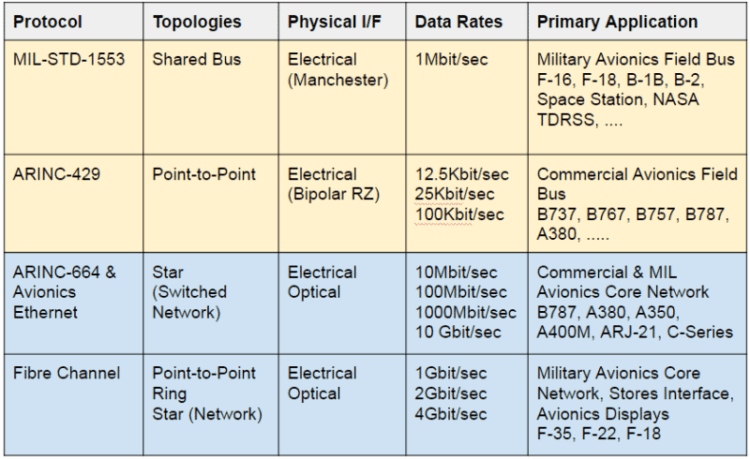

Common avionics data bus and network technologies featured on in-service aircraft and spacecraft. Photo courtesy of Avionics Interface Technologies

Today’s avionics testers are addressing the needs of complex boxes and architectures, but challenges remain in areas such as cyber protection, fiber optics, productivity, versatility, size and no-fault-founds (NFFs).

Cyber is emerging as a big driver, said Troy Troshynski, VP of marketing and product development with Avionics Interface Technologies (AIT), a player in data-bus testing. He expects to see more of an emphasis on cyber protection from the military, especially in large depot test programs, but that “flows down to us even at the instrument level.”

“You’re taking all of these systems and subsystems off an aircraft and putting them on trays and connecting them to [test] systems,” he said. “So the first thing is, we’ve got to secure these [test] systems, so that they’re not infecting the aircraft systems.”

Avionics bus and network test instruments also need to be protected from hacking. And test data needs to be secured “when it resides in the [tester] and when it’s used and passed on to other systems.”

Troyshynski also anticipates that more testing will be done on board aircraft. It’s a question of when, not if. As avionics test equipment continues to decrease in size, weight and power, it will become increasingly economical “to have [it] become part of the actual aircraft.” As the data infrastructure — aircraft network connectivity — advances, at “some point soon both of these trends will converge and the benefits … will outweigh the costs.”

Operators also are keen to reduce the NFF problem, which stresses the repair pipeline and creates uncertainty as to which boxes are really good. NFFs cost airlines $250,000 per aircraft per year, said Ken Anderson, CEO of Universal Synaptics, a provider of intermittent testers. For a large fleet, that’s a loss of about $40 million a year, he added. Anderson also cited a 2015 statement by a former deputy assistant secretary of defense that NFFs were costing the services more than $2 billion a year.

Given the looming technician shortage, in coming years there will be fewer people on the ground to keep airplanes in the air, said Lew Wingate, VP of distribution and ground support test equipment for Barfield. “They will need easier, faster and more cost-effective equipment” in order to meet key productivity and NFF targets.

One step along that path is a recent upgrade to the tablet-based remote controller of the company’s DPS1000 air data test set equipment, allowing technicians to access component maintenance manual and aircraft maintenance manual documentation. Barfield also has partnered with Universal Synaptics to distribute the latter’s wire-bundle and box-level intermittent fault testers in the commercial market.

“As much automation as possible” is a good thing, along with removing “Murphy” from the equation, said Scott Brooks, director of avionics solutions at Pentastar Aviation. Automation has improved functions such as air data test, removing the possibility of damaging an aircraft’s altimetry and airspeed sensors if the test equipment is used incorrectly, he added.

Air data test rival, ATEQ Aviation, also features tablet-based wireless control. Patrick Brousseau, ATEQ’s sales manager, said the company’s ADSE 650 product is at least half the size of other units. The tablet “connects” to a wireless transceiver built into the instrument, but it’s not using the internet.

The next big change in this niche will come when aviation moves to digital sensors, he said. “But I would not even imagine 10 years being enough time” for the industry to get to that point.

This story is part of an article focusing on future challenges for automated test tools. Read the full article in our October/November issue.