Global Avionics Round-Up from Aircraft Value News (AVN)

Image courtesy of Duncan Aviation

For more than a decade, regulators have hailed Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B) In as the next step in airspace efficiency, promising richer situational awareness, tighter traffic spacing, and faster responses in congested skies. Pilots and air traffic controllers have long nodded along to the theory.

However, in airline operations rooms, the conversation is more grounded: downtime, maintenance cycles, and capital budgets. If a mandate for ADS-B In retrofit ever comes to pass, the real question is how the retrofit reality will play out across short-haul and long-haul fleets—and how disruptive it might be compared to the upgrades that have come before.

The Long Road to “In”

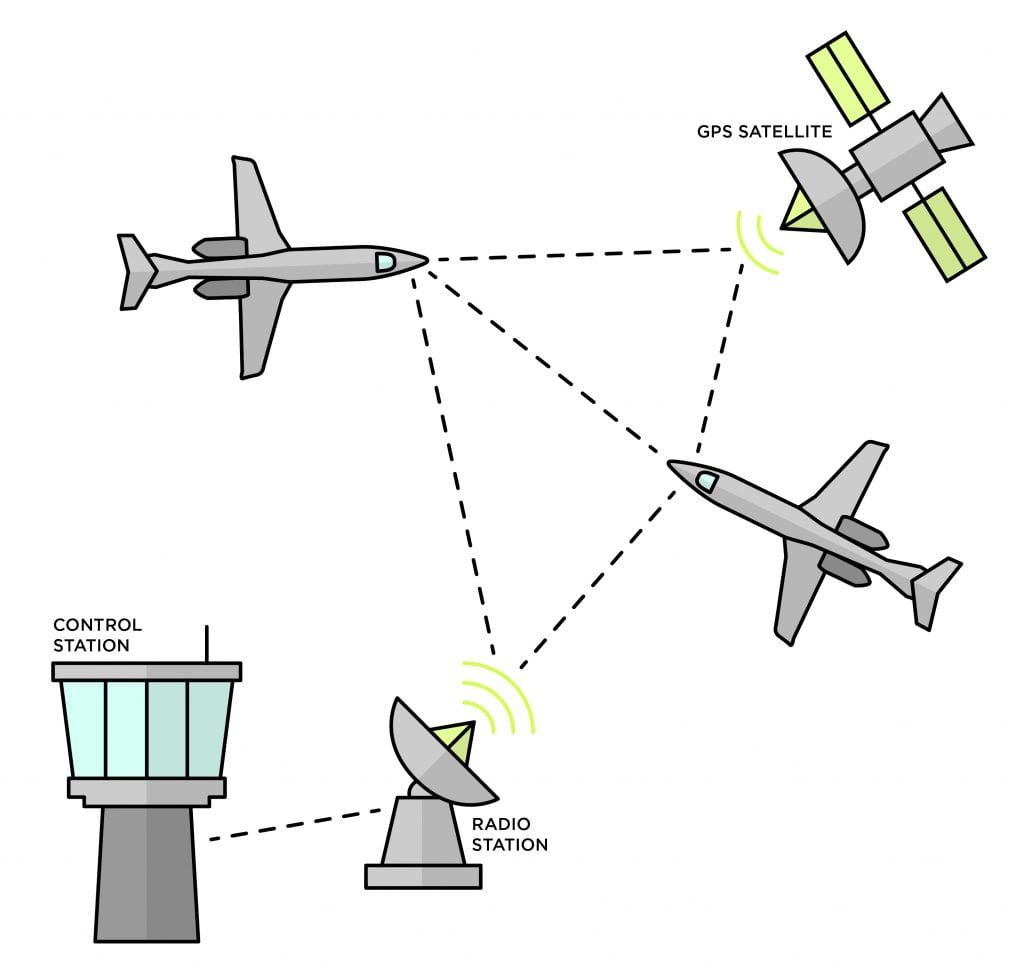

ADS-B is split into two halves: Out and In. ADS-B Out has already been widely implemented; aircraft broadcast their position, velocity, and intent to ground stations and other aircraft. ADS-B In, the more interactive half, allows aircraft to receive this data, displaying traffic, weather, and other information on cockpit screens.

Regulators tout the benefits: collision avoidance, improved arrival sequencing, and enhanced situational awareness in remote airspace. But while the aviation world has talked about ADS-B In since the mid-2010s, adoption has lagged, largely because airlines see the price tag and the operational complexity.

Retrofit costs are not trivial. For narrowbodies like the A320neo or B737 MAX, the price per aircraft for an ADS-B In-capable avionics upgrade can run from $50,000 to $150,000, depending on whether existing displays and wiring can support the new capability.

Widebodies like the B777 or A350 face higher costs, sometimes double, due to more complex cockpit systems, additional wiring, and integration with flight management computers. For fleets numbering in the hundreds, the line items add up fast.

Short-Haul Realities: Tight Windows, Tight Budgets

Short-haul fleets are the first place the retrofit question hits hardest. Airlines operating dense schedules—think Ryanair, Southwest, or easyJet—rarely have an aircraft sitting idle long enough for a full avionics upgrade without disrupting service.

Retrofitting ADS-B In is unlikely to be a “plug and play” affair; installation often requires taking the aircraft out of service for multiple days to a week, depending on hangar access and availability of qualified technicians.

Some airlines may attempt to phase retrofits into scheduled heavy maintenance checks, typically C or D checks. That approach minimizes downtime but stretches the timeline over years. For low-margin carriers, the timing of these checks is also a budgetary puzzle.

Spending $100,000 per aircraft now might mean deferring other upgrades, such as Wi-Fi enhancements or cabin refreshes, that passengers see more directly. In this sense, ADS-B In is a classic behind-the-scenes technology: critical for safety and efficiency, yet invisible to the paying customer and therefore harder to justify in tight financial cycles.

Long-Haul Fleets: Complexity Meets Opportunity

For long-haul fleets, the retrofit calculus is different but no less complicated. Widebody aircraft often operate on thinner schedules, giving airlines more flexible windows to install new systems during overnight or multi-day stops.

Still, integration is more complex. The avionics suites in aircraft like the B787 or A350 are highly integrated, meaning that adding ADS-B In can trigger software updates across multiple systems. Testing and certification for these aircraft often takes longer, sometimes requiring manufacturer support to verify that the retrofit doesn’t interfere with existing navigation or traffic collision systems.

The upside is that widebody aircraft usually have higher revenue potential per flight. If ADS-B In improves operational efficiency, airlines can recoup retrofit costs more quickly than with high-utilization short-haul aircraft. And because long-haul aircraft often traverse airspace where ADS-B coverage is patchy, pilots stand to benefit more from traffic and weather feeds than on short domestic hops.

An ADS-B Out equipped display system from Avidyne. (Photo: Avidyne)

Retrofit Disruption: Past Lessons

To gauge the likely disruption, it helps to look back. Connectivity upgrades, like in-flight Wi-Fi retrofits, were often a mix of downtime, software updates, and passenger communication headaches, but they were relatively straightforward electrically.

New surveillance mandates, such as Mode S transponders or TCAS upgrades, hit similar operational bumps. ADS-B In sits somewhere between these examples. It’s more invasive than Wi-Fi but less so than a full avionics overhaul, like installing a new flight management system.

Airlines will likely adopt a phased approach, prioritizing aircraft that operate in high-density airspace first. Expect initial disruptions, particularly in short-haul fleets, but they are likely manageable with careful planning and staged implementation. Over time, the retrofit should integrate into standard maintenance schedules, much like engine health monitoring systems or upgraded weather radar packages have.

Ultimately, the ADS-B In retrofit story is a story of trade-offs. Airlines must weigh the upfront cost, downtime, and planning headaches against long-term efficiency, fuel savings from optimized spacing, and enhanced situational awareness.

Regulators are pushing for a safer, more connected sky, and the technology promises real operational benefits. But in the short term, operators will feel the pinch, particularly on short-haul networks where every day on the ground carries a revenue hit.

This article originally appeared in our partner publication, Aircraft Value News.

John Persinos is the editor-in-chief of Aircraft Value News.