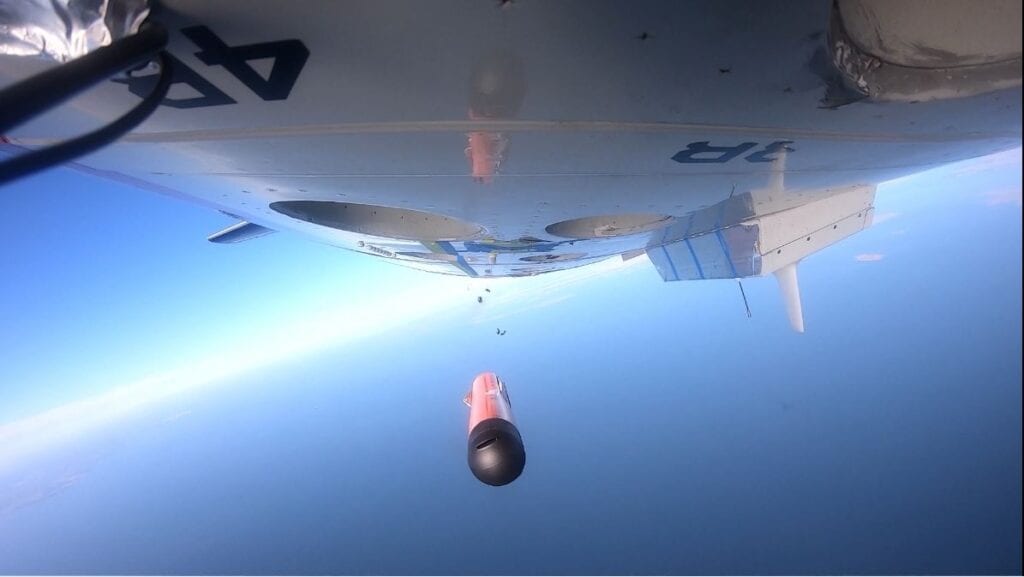

In January NOAA tested of one of these UAS, an Altius-600 made by Area-I, in a clear air test at Naval Air Station Patuxent River’s test range. (NOAA)

Sixteen years ago an experimental unmanned aircraft system (UAS) was launched into tropical cyclone Ophelia. Now the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is working to develop new specialized UAS to deploy into hurricanes and gather data previously inaccessible to scientists.

“When these storms make landfall, they impact buildings, they impact us, so we want to know what those winds are really close to the surface,” Dr. Joe Cione, lead meteorologist for NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Lab Hurricane Research Division told Aviation Today. “The P-3 we fly goes about 10,000 feet but can’t get low because of safety concerns. It’s just not practical. You’re not gonna have a manned aircraft with 20 souls on there, going down, and flying 100 feet off the deck with 60, 50, 30-foot waves and 100-mile per hour winds. So that’s why we want to use drones to safely get down there.”

In the very early stages of using UAS to study hurricanes, aircraft would be sent to where scientists thought a hurricane might occur and then they would wait to see if the hurricane would interact with the UAS, Cione said. In 2014 these missions became more sophisticated with the use of two Coyote UAS from the Navy which was launched from NOAA’s WP-3D Orion Hurricane Hunter.

NOAA researchers will use the WP-3D Orion Hurricane Hunter to deploy the drones into hurricanes. (NOAA).

The experiments with the Coyote UAS created a proof of concept for NOAA to show that this technology worked, however, the Coyote UAS were created for the military so NOAA wanted to field aircraft that were designed with its missions in mind, Cione said.

“What we’re trying to do is validate a new technology that will enable us to gather meteorological data in a portion of the storm that we currently have very little means to capture that data from,” Lt. Cmdr. Adam Abitbol, NOAA Corps test pilot and WP-3D Orion aircraft commander for test flights deploying the Altius UAS, said. “So, what this will allow us to do is collect an immense amount of new data in one of the very highly sought after areas of the hurricane or tropical storm which is called the boundary layer. That area that is kind of closest to the ground and currently to get information or meteorological data from that boundary layer is quite difficult and not only difficult but we can not get very much of it.”

Currently, NOAA uses dropsondes, which are sensors tethered to parachutes, to get data from hurricanes, however, there is no controlling where they go after they are launched. UAS would be able to deploy to different parts of the hurricane and gather more information. Cione described it as watching a movie versus looking at a picture.

“So you can think of it as a movie versus a picture kind of analogy, and the drones give us more of a movie,” Cione said. “So, the movie part of it is really useful for what we call situational awareness so we send this data directly to the hurricane center, and when the hurricane center gets it, they use it for their public forecasts and they also interact with emergency managers to make life or death decisions for landfalling storms. So if we can give them a better picture of what’s happened, particularly with the wind, emergency managers and other professionals can have a better opportunity to make these more informed decisions.”

NOAA test pilots Lt. Cmdr. Becky Shaw and Lt. Cmdr. Adam Abitbol in flight station of WP-3D Orion during Altius flight test in January. (NOAA)

Once the UAS is deployed from the P-3, it can either be flown by an operator onboard or fly autonomously according to a pre-programmed flight path., Abitbol said.

“After launching from the aircraft, it’ll have both autonomous control and command and control from the P-3,” Abitbol said. “So we’ll have an operator onboard the P-3 that can manipulate the UAS, that can capture all the data, or we can also send it into a pre-programmed flight path, and it will go down to where we want it to go and collect all the data.”

In January NOAA tested one of these UAS, an Altius-600 made by Area-I, in a clear air test at Naval Air Station Patuxent River’s test range. The Altius-600 is a 27-pound aircraft with a nine-foot wingspan. NOAA is using a build-up approach to test these UAS, Abitbol said. The first test of this UAS occurred in 2019 and looked just at the ability to safely launch a UAS from the P-3. The January demonstrations were more complex but still occurred under normal weather conditions.

“Okay, now that we know we can launch it, can we control it from the plane,” Abitbol said. “How far away can we be? Within what range will the sensors still send data? Can we control the aircraft? Is there any orientation at which our plane and the UAS wouldn’t communicate with each other? So we went through a variety of tests to make sure that once we do employ this in the operational environment that is going to be ready and we know what to expect and the behavior of the UAS.”

This hurricane season NOAA will complete operational environment tests where they deploy the UAS into a hurricane, Abitbol said.

“This year will be another full year of testing in the hurricane environment to make sure that, hey, it’s doing what we asked it to do, it has the expected behavior, and the data is accurate and precise exactly what we’re looking for,” Abitbol said. “So once we are able to validate that in the storm environment, upon the completion or conclusion of that, then we’ll be ready to go into full operational use which will be hopefully the 2022 hurricane season.”

Researchers on this project used the Coyote tests to decide requirements for these new UAS, Cione said. NOAA is focused on improving the duration and range of the Coyote UAS tests. The goal is to be able to fly for four hours and at least 150 miles from the P-3.

“Our staff does not want to babysit a drone,” Cione said. “…We want to air deploy a drone. We want it to go at least 150 miles from the aircraft. We want it to last hours, not an hour, and we want it to have the same payload that we use for our balloons and for our dropsondes.”

The Altius-600 was able to get as far as 190 miles away from the P-3 during the January flight test, Cione said. They were not able to test the full duration because of time constraints but they believe it will be able to get between three and four hours of duration.

Another area NOAA researchers were looking for improvements in from the Coyote UAS was its buffering abilities. Cione explained that the Coyote UAS were unable to get further than 20 miles from the P-3 without losing communications. If the P-3 and UAS were 22 miles apart they would lose communications and that data that the UAS had been collecting.

“We didn’t have a buffering system on there so if we got to 22 miles, we just lost a day, that was it,” Cione said. “It was very painful. However, all of these systems, that was another requirement…have to have buffering. So, for whatever reason, we’re out of range, we can’t do it, it goes beyond the 150 miles, the P-3 goes somewhere else, so long as we come back and it buffers it, it’ll send the data back to us.”

Cione said they are also looking at the possibility of having an onboard radio on the UAS to use satellite communications.

Because these UAS are being fielded specifically for hurricane hunting, they will have to have weatherproofing specifications unlike the previous Coyote drones which were made with military specifications, Cione said. NOAA wants these UAS to fly consistently below 1,000 feet where they will deal with high winds, lots of turbulence, and sea spray.

“So they have to be able to withstand hard turbulence and they have to be weatherproof, those are the two biggest things I would say so water doesn’t get into the electronics,” Cione said. “Also you have to make sure that the payload is really well isolated from any electromagnetic interference from the engine that’s running. It also has to be very careful about what we’re sampling is actually real meaning that the airflow is not influenced by the aircraft itself.”

While the Altius-600 was used in the January flight test, it is not the only UAS NOAA is testing for this mission. They are also testing Black Swift’s S1 UAS which is three pounds and a nine-pound UAS made by Barron Industries.

The benefits of these missions will be two-fold. The data gathered by these UAS will be used immediately to track hurricanes. It will also be used to improve future hurricane modeling, Cione said.

“The immediate payoff of using something like drone technology gives us a lot more observations, movie verse snapshot, and gives us a better indication of what the winds are especially as we’re getting close to landfall,” Cione said. “And then a slower roll impact is we can improve our understanding, and then future, you have to do model development. So it’s months to years, but you can eventually improve the models to give you a better future forecast for intensity change. So it’s a kind of a help me now, and then help me later kind of approach.”