The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) plans to re-use algorithms employed in the recent AlphaDogfightTrial (ADT) for research on artificial intelligence-enabled intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); electronic warfare (EW); decision-making; and other purposes.

In ADT, eight industry teams pitted their AI dogfighting agents against one another in F-16 simulators and against U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps pilots in a lab environment.

“We look forward to applying all the technology that we explored and built up as part of this trial in other domains,” said Air Force Col. Dan “Animal” Javorsek, the ACE program manager of Air Combat Evolution in DARPA’s Strategic Technology Office and a former F-16 pilot. “Because it is reinforcement learning, the algorithms aren’t limited to the air-to-air combat scenario. We’re also looking to apply them to ISR, EW, decision making, and other autonomous vehicles.”

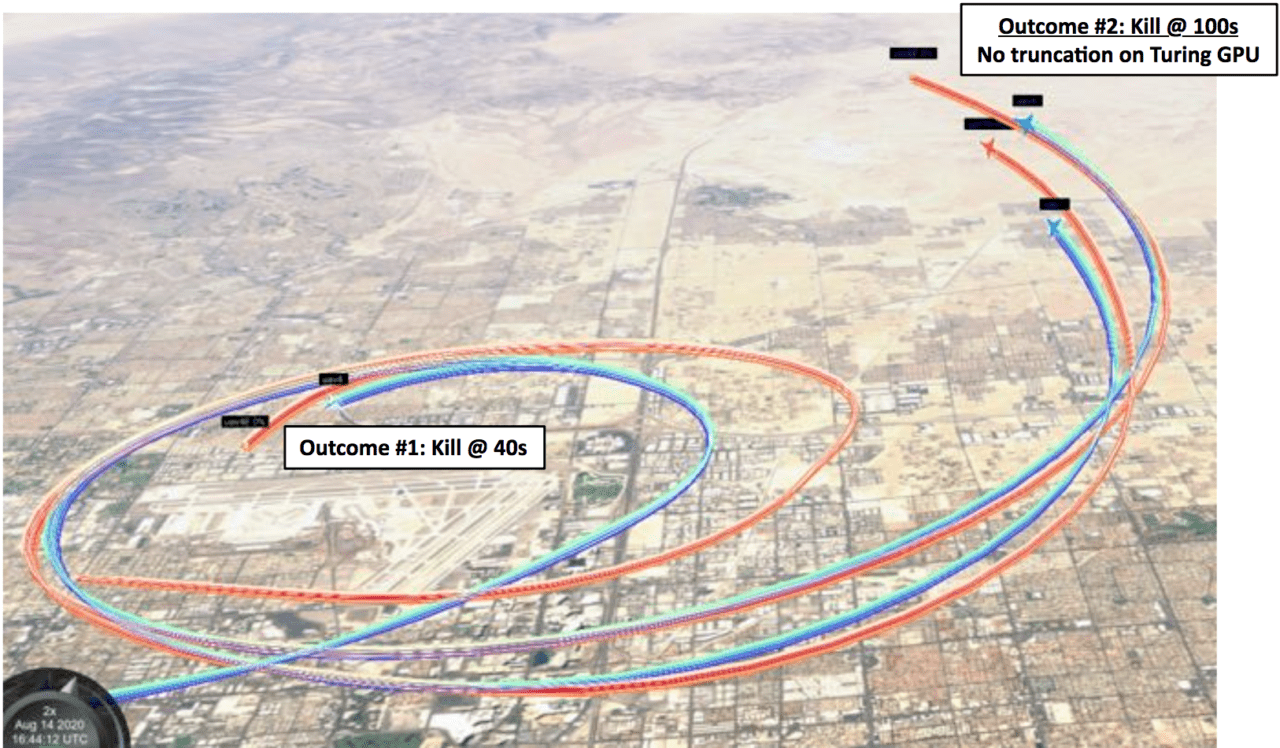

Heron Systems, a small AI firm located near Patuxent Naval Air Station, Md., took first place in ADT. To win the final round, Heron’s AI agent, “Falco,” took out in five separate dogfights an F-16 simulator helmed by “Banger,” an elite F-16 pilot, a graduate of the Weapons Instructor Course (WIC) at the U.S. Air Force Weapons School at Nellis AFB, Nev.

Heron also beat out Lockheed Martin, which took second place, and six other competitors.

The other competitors in order of finish were Boeing‘s Aurora Flight Sciences, which took third; PhysicsAI; SoarTech; Georgia Tech Research Institute; EpiSys Science, Inc., and Perspecta Labs.

Heron’s performance was dominant, as it frequently was able to gain first shot, high aspect basic fighter maneuver (HABFM) gun kills at 3,000 feet or less against rivals.

ADT has been a year-long risk reduction effort for DARPA’s Air Combat Evolution (ACE) program, which aims to increase fighter pilots’ and others’ trust in combat autonomy by using human-machine collaborative dogfighting and to make advances in complex human-machine collaboration.

One topic under consideration is the addition of a number of AI, collaborative agents to future scenarios in which one AI agent could control other agents, said Adrian Pope, an AI research engineer with Lockheed Martin.

While there are a number of technical challenges, such as the multi-agent one, to future AI military use, the largest may be cultural. Feedback on ADT featured a demographic split.

“There’s a bi-polar response from the aviator community,” Javorsek said. “The digital natives, the younger generation coming into cockpits these days, have a lower reluctance to these sorts of [AI] systems. The older pilots took pride in the ability you had to fly the airplane and control where the radar was pointing. Naturally, that’s not a very good application of that cognitive human capacity in the aircraft because it means while the pilot is controlling the elevation of the radar, the adversary could be doing something you’re not paying attention to or thinking about. We’re trying to offload as much of that [as possible].”

At the core of the ACE program and future military AI efforts is the proper calibration of trust in AI and autonomous systems.

“Whereas the older community tends to under-trust autonomy to include these life-saving systems, like Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance, which took 40 years to get onto an all-digital airplane, we have a pretty high risk that the younger generation may tend to over-trust,” Javorsek said.