Global Avionics Round-Up from Aircraft Value News (AVN)

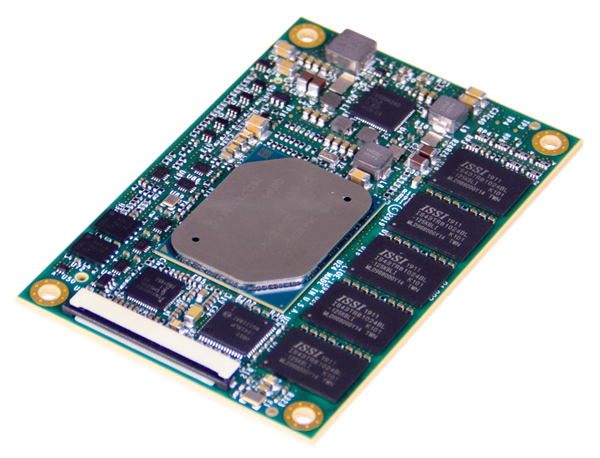

In January 2020, Mercury Systems, Inc. unveiled its CIOE-1390 multi-core processor module for helicopters and urban air mobility vehicles (Mercury Systems, Inc. Photo)

Avionics used to be the realm of reliable but incremental upgrades — new radar here, a better flight management system there.

Today, the real leap is happening inside the silicon: ever‑faster processors, multi‑core systems‑on‑chip (SoCs) and advanced heterogeneous architectures are transforming aircraft cockpits into sophisticated mission systems.

This transformation matters not just for safety or efficiency; it’s increasingly influencing aircraft values and lease rates.

Consider the business‑jet market. Bombardier recently introduced an “Advanced Avionics Upgrade” (AAU) for in‑service Global 5000/6000/5500/6500‑series aircraft, powered by its Vision flight deck and avionics partner Collins Aerospace.

The upgrade brings the new Combined Vision System (CVS), blending synthetic vision and enhanced vision into one display. The result: crews get much clearer situational awareness, even in poor weather, and operators get an aircraft that looks far more modern. That in turn supports higher residual value and better lease marketability.

Behind that visible upgrade is a deeper shift: avionics processing workloads are growing fast. Modern synthetic vision, terrain‑awareness, predictive weather, datalink communications, ADS‑B decision support, sensor fusion—all these require processors with much greater throughput, lower latency and smarter cooling.

Academic work confirms this. One recent study on multi‑processor systems‑on‑chip (MPSoCs) for avionics shows how thermal constraints and task‑allocation across heterogeneous cores matter for safety‑critical avionics workloads.

That hardware trend is percolating into the marketplace. For example, upgrades such as those from Collins for the King Air and Hawker fleets explicitly pitch “advanced communication, navigation and surveillance tools” and modern displays.

The Cost of Older Chips

For lessors and operators, this means something quite concrete: if your aircraft’s cockpit is running on a chip‑architecture designed a decade ago, you may face shorter remaining useful life, lower asset value, and reduced lease rate expectation.

The OEM‑upgrade proposition now often carries the tagline of “asset value retention” as a driver. For instance, in the Boeing structural upgrade page, under avionics upgrade benefits, one bullet is “Asset value retention with our solutions for your leased aircraft.” In other words, faster chips don’t just change the flight deck; they change the balance sheet.

Why have chips accelerated so much? Several factors converge.

First, the cost‑curve of high‑performance embedded processors has improved, allowing avionics manufacturers to move from closed‑boxed control units to multi‑core systems running integrated sets of functions (e.g., navigation, surveillance, communication, and mission‑management).

Second, the regulatory and certification path is maturing: although avionics software remains highly certified, modular architectures (and abstraction layers) are allowing faster hardware refresh.

Third, the push towards connected and even semi‑autonomous flight means avionics need greater computation power for data‑fusion and decision‑support, not just for display or radio. Along those lines, Honeywell International and NXP Semiconductors are partnering to bring a new chip architecture into Honeywell’s Anthem cockpit system for autonomous flying.

What does that mean for aircraft values and lease rates? Consider a mid‑life business jet. If the cockpit upgrade is available, the operator might spend a few hundred thousand dollars to bring the avionics current, but they can often secure a higher lease rate or command better trading terms because the aircraft becomes more future‑proof.

Conversely, without the upgrade, that aircraft may sit on the market with operators demanding discounts or shorter leases (to hedge obsolescence risk). In fleet leasing, this has a ripple effect: lessors price in not just airframe hours, but avionics obsolescence risk. As avionics processing demands rise, older cockpits become a liability.

Let’s say a large regional airliner or business‑jet lessor evaluates two aircraft of the same model, engine‑time and calendar, but with different avionics. The one with modern computation capabilities, connectivity, and a data‑rich cockpit will likely fetch a higher residual value (perhaps 5%‑10 % more) and command a higher lease rate (perhaps spread over the lease term). Over the life of the lease, that difference matters.

The chip era in avionics has arrived. Faster computation enables richer functions, smarter cockpits and higher margins for OEMs. For operators and lessors, it means cavalier thinking about avionics no longer cuts it.

If your aircraft’s brain is outdated, your asset value and lease potential may shrink. And if you invest in upgrades today, you can capture a premium tomorrow. The cockpit has become not just a functional element; it has become a value barometer.

The article first appeared in Aircraft Value News.

John Persinos is the editor-in-chief of Aircraft Value News.