The Indonesian National Transportation Safety Committee (KNKT) final Lion Air JT610 737 MAX accident investigation report lists 89 findings explaining what factors caused the aircraft to crash and kill all 189 flight crew and passengers onboard during an October 29, 2018 flight from Jakarta to Pangkal Pinang on the island of Bangka. Photo: KNKT

Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee (KNKT) published its final 322-page accident investigation report on the October 2018 Lion Air Boeing 737 MAX flight JT610 crash, finding that it was caused by a combination of an improperly aligned angle of attack (AOA) sensor, lack of pilot reporting and training as well as a breakdown in safety oversight of certification and design flaws shared between Boeing and the FAA within the aircraft’s maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) system.

The report does not explicitly state a singular cause for the crash, but instead lists a total of 89 findings that KNKT investigators discovered about a multitude of factors that caused the JT610 crash to kill all 189 passengers and flight crew onboard. New revealings in the report include the discovery of the reason the AOA sensor was feeding faulty information to the flight control computer was that it was most likely improperly repaired by a U.S.-based maintenance repair facility.

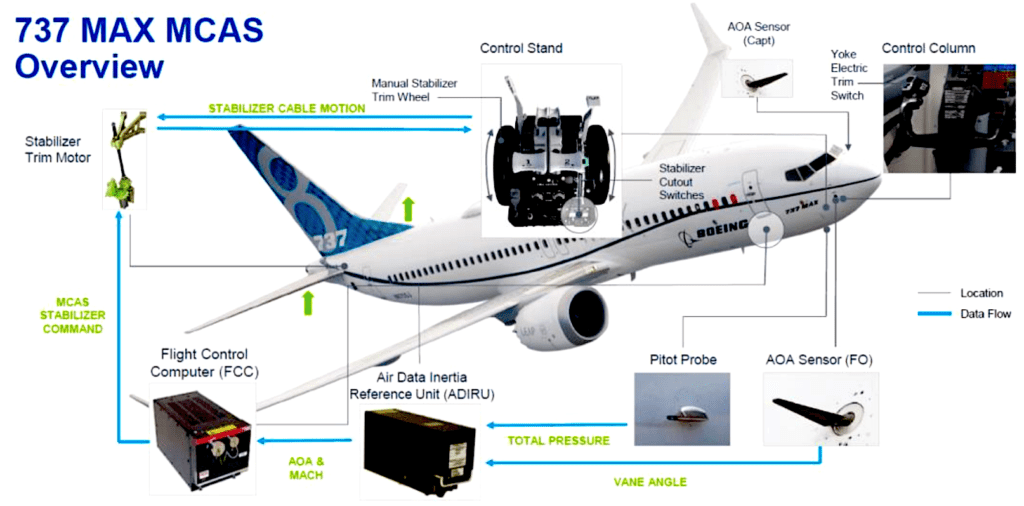

A major focus of the findings revolves around the MCAS system, which was originally designed to automatically command the aircraft’s nose-down stabilizer to enhance pitch characteristics when entering steep turns with elevated load factors and flaps up conditions that are approaching stall, according to Boeing. It becomes deactivated once the angle of attack falls below the threshold or when manual stabilizer commands are input by the flight crew.

According to the KNKT-lead investigative report, as the development of the MAX neared completion, functionality of MCAS was expanded to lower Mach numbers and “increased to a maximum MCAS command limit of 2.5 degrees of stabilizer movement.” When the MAX underwent the functional hazard analysis phase of its certification campaign, unintended MCAS-controlled stabilizer was considered to be “Major”, which prevented further analysis of its failure conditions and the reasoning by Boeing that uncommanded MCAS functionality could be countered by stabilizer trim and stabilizer cutout.

ABOVE: An overview of how the stab trim cutout procedure was used on the flight occurring prior to the JT610 flight as featured in the final report. BELOW: An image depicting how the 737 MAX’s horizontal stabilizer system works, as featured in the final report. Photo: KNKT

When incorrect AOA sensor input is transmitted to the 737 MAX flight control computers, the MCAS system can become unintentionally activated producing a cascading string of effects that if not properly corrected by the pilots, can lead to extreme difficulty in controlling the aircraft. In the case of JT610, the misaligned angle of attack sensor further complicated the situation.

“During the accident flight erroneous inputs, as a result of the misaligned resolvers, from the AOA sensor resulted in several fault messages (IAS DISAGREE, ALT DISAGREE on the PFDs, and Feel Differential Pressure light) and activation of MCAS that affected the flight crew’s understanding and awareness of the situation,” the report said.

A key disclosure in the report is the review of flight operations quality assurance (FOQA) and maintenance records for the JT610 aircraft showing that in October 2017, the right-side AOA sensor it was operating with was repaired by Miramar, Florida-based Xtra Aerospace. A work order cited in the report notes that the goal of the repair was to prevent the appearance of erroneous speed and altitude indications on warnings on the primary flight display. A record describing the repair showed that an eroded vane—which is used to measure the aircraft’s angle of attack and potential to stall—on the sensor was replaced, tested and calibrated to be shipped back to Lion Air.

However, the report states that the investigators could not find proper record-keeping from Lion Air about how the AOA sensor was calibrated. After the sensor was repaired, it was not actually installed on the JT610 aircraft until Oct. 28, 2018 during a repair–one day prior to the fatal Oct. 29 JT610 flight. Prior to the JT610 flight, the sensor was operated on another flight, LNI043, where similar problems occurred to what ultimately plunged JT610 into the Java Sea.

“On the subsequent flight, a [21-degree] difference between left and right AOA sensors was recorded on the DFDR, commencing shortly after the takeoff roll was initiated (note it takes some airflow over the vane for the vanes to align with the airflow). This immediate [21-degree] delta indicated that the AOA sensor was most likely improperly calibrated at Xtra Aerospace,” the report said.

Several hours after KNKT published its report, the FAA issued a statement revoking the Part 145 repair station certification of Xtra Aerospace.

“Xtra failed to comply with requirements to repair only aircraft parts on its list of parts acceptable to the FAA that it was capable of repairing. The company also failed to comply with procedures in its repair station manual for implementing a capability list in accordance with the Federal Aviation Regulations,” the FAA said in its statement.

The agency’s decision to revoke Xtra’s license was a separate action from the KNKT investigation, and was issued as part of a settlement agreement with the company. In an emailed statement submitted to Avionics International, a representative for Xtra Aerospace provided clarification on why the agency’s decision to revoke their license and the publishing of the report was two separate incidents.

“We have been cooperating closely with the FAA throughout its investigation and though we have reached a settlement with the FAA, we respectfully disagree with the agency’s findings. The FAA’s enforcement action is separate from the KNKT’s investigation and report of the Lion Air Boeing 737 Max accident and is not an indication that Xtra was responsible for the accident. Safety is central to all we do, and we will continue cooperating with the authorities. We would like to express our deep sadness and sympathy for all those who have lost loved ones in the Lion Air Flight 610 accident,” the representative said.

Lion Air is also cited by KNKT’s report for improper record keeping and pilot reporting that could have identified problems with the JT610 MAX’s MCAS system, even though pilots were never trained or briefed on the functionality of the MCAS system. A review of flight data recorder data on the flight prior to the Oct. 29, 2018 flight, the same aircraft registered as PK-LQP operated a scheduled passenger flight, LNI043, on Oct. 26 from Tianjin, China to Manado, Indonesia.

During that flight, the captain’s primary flight display erroneously showed speed and altimeter flags. That lead to the replacement of the aircraft’s AOA sensor with the one repaired by Xtra Aerospace that had the 21-degree bias, which was actually undetected by Lion Air’s maintenance team.

The next flight of PK-LQP would take it from Manado to Jakarta where it would eventually perform the fatal Oct. 29 flight the next day. On the flight from Manado to Jakarta, the flight crew experienced the activation of the MCAS system and left control column stick shaker that remained active throughout the flight. That flight also featured primary flight display warning messages showing disagreements between the indicated airspeed and altitude readings. That flight crew stopped the activation of the MCAS system by switching the MAX’s stabilizer trim to “cut out”, according to the report.

Although the flight crew reported malfunctions to the maintenance team once they landed, they did not report the activation of the stick shaker and how they moved the stab trim to cut out. The JT610 flight crew experienced the same MCAS problems as the previous flight crew, however they did not identify the runway stabilizer, according to investigators.

“In the event of MCAS activation with manual electric trim inputs by the flight crew, the MCAS function will reset which can lead to subsequent MCAS activations. To recover, the flight crew has 3 options to respond, if one of these 3 responses is not used, it may result in a miss-trimmed condition that cannot be controlled,” the report said

As a result of the investigation’s findings, KNKT issued safety recommendations to Lion Air, Batam Aero Technic—the company that installed the improperly calibrated AOA sensor in Denpasar—AirNav Indonesia, Xtra Aerospace, Boeing, Indonesia’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) and the FAA. Boeing specifically is recommended by the investigators to consider the impact of flight deck alerts and indications and the human factors associated with them relating to how pilots will respond to certain messages or alerts when their workload increases.

In a statement issued by Boeing following the release of KNKT’s final report, the manufacturer acknowledged the recommendations and described how the interactions between aircraft’s AOA sensors and and MCAS flight control software work.

“Going forward, MCAS will compare information from both AOA sensors before activating, adding a new layer of protection. In addition, MCAS will now only turn on if both AOA sensors agree, will only activate once in response to erroneous AOA, and will always be subject to a maximum limit that can be overridden with the control column,” Boeing said in the statement.

An eventual return to service of the 737 MAX is still undetermined, although upon reporting its third quarter earnings on Oct. 23, Boeing indicated it is still anticipating that to occur in the fourth quarter of 2019. Amid the investigation, Boeing replaced Kevin McAllister with Stan Deal as the new president and CEO of its commercial airplanes division.

UPDATE: Please note that the article has been updated with a statement provided by a representative for Xtra Aerospace and to clarify that while the repair of the AOA sensor was conducted by Xtra, the actual installation and lack of record keeping about its status is attributed to Lion Air, not Xtra, in the KNKT report.