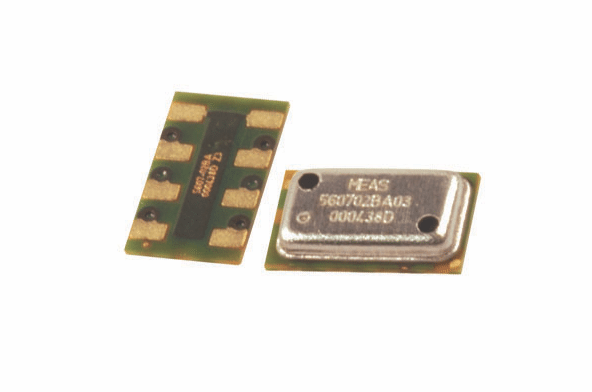

The TE Connectivity MS5607 altimeter for UAS. Photo courtesy of TE Connectivity

Artificial intelligence and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have a bright future within the aviation industry. While standard use of that technology seems like it is decades away, it could be closer than you think. There have been some demonstrations:

- A GE Aviation engine mechanic recently tested a Wi-Fi-enabled torque wrench, using it to “optimally” tighten bolts, as the company said.

- Microsoft is testing a sailplane that it hopes will be able to fly itself without a motor by intelligently catching rides on naturally occurring thermals.

- Boeing recently invested in Texas-based AI and machine-learning company SparkCognition.

- Bombardier is spending some $700 million over the next six years to continue using IBM services, which includes IBM’s Watson.

Another industry on the cusp of using artificial intelligence and IoT together to provide services to customers is the unmanned aircraft systems industry — as TE Connectivity’s senior manager of sensor product knowledge and training, Pete Smith, sees it.

“Drones are going to become part of IoT networks. There’s no doubt about it. I think they are in a lot of places already,” Smith told Avionics. “Essentially, IoT is the proliferation of sensors to keep track of things and take data. And all these sensors take all this data and transmit it all back to these big data warehouses. Most of it is in the cloud right now.”

TE Connectivity supports a variety of industries with a variety of different products. But the company’s sensors business unit makes products for the military, general aviation and commercial markets. TE Connectivity also focuses on making sensors for drones: altimeters, airspeed indicators, tilt sensors and angle sensors, to name a few.

Although the company declined to name any of its customers, Smith named two drone operations in which sensors enable artificial intelligence: agriculture and long-linear infrastructure inspection.

BNSF Railway has been at the forefront of using UAS to collect data for inspection. With miles and miles of railroad tracks, using a drone is the most efficient way to conduct inspections. In 2015, BNSF Railway used a drone from Boeing’s Insitu to fly several missions. During those initial demonstrations, the need for purpose-built sensors and systems was realized. The railway needed the drones to take pictures with a quarter-inch resolution from 350 feet away at 40 knots. Aggregated, the imagery comes to about 300 gigabytes at two shots per second, building an overlapping map of hundreds of miles of track. Furthermore, BNSF needs technology capable of reading the data quickly. The railway company has co-developed analytics software, “Rail Vision,” that can assess track conditions using the overlapping images.

“They can pre-program [the drone] to actually follow the tracks and while it’s following the tracks. It’s collecting data. It has cameras on board taking pictures of the tracks. It’s taking huge amounts of data; these are high-resolution cameras. And what’s happening now is they’re using artificial intelligence to do analytics on the data,” Smith said of railroad track inspections in general. “Because it’s such a huge amount of data, they need to bring in artificial intelligence so that they can look at the tracks. And some of these drones are getting artificial intelligence imbedded in them already. The drone starts to do some of the analytics in real time. It tells you that the tracks are in good condition, that none of the ties are broken, if there’s any gaps or un-level places on the road bed.”

One company providing agriculture services with drones is Hawk Aerial. At Hawk Aerial’s base in the Napa County region of California where vineyards are plentiful, the company has partnered with VineView Scientific Aerial Imaging and SkySquirrel Technologies on vineyard management services. Hawk Aerial uses a SkySquirrel drone with a Quanta camera to collect data that is converted to analytical maps, like VineView’s calibrated enhanced vegetation index.

“Real estate photography — you know any kid with a [DJI] Phantom can go do that. There’s tons of competition, and prices are very low,” Hawk Aerial CEO Kevin Gould told Avionics sister publication Rotor & Wing International earlier this year. “What we do is very, very specialized. In fact, we don’t have legitimate competition. And the reasons [for that] are the sensors that we use and [the fact that] the processes for picking these images and making them into specialized maps is proprietary.”

Where can TE Connectivity sensors come into play? Should a drone be employed to deliver a contour map, its flight path needs to be precise for an accurate map.

“The drone has to fly at exactly the right altitude to develop this contour map, and this is where our altimeter plays a critical part,” Smith said. “[The map] actually gives you an outline of the field where the hills and the valleys and the high points and the low points are.”

One of the next steps in the advancement of sensors is wireless. While the aviation industry has recently started migrating to the use of wireless avionics intra-communication (WAIC) technology, TE Connectivity has been readying to meet potential demand. When sensors are hardwired, especially in an industrial application, Smith explained, wires have to be run through a central control unit. This requires the compliance of electric codes, and the general process is usually expensive. Wireless sensors, he continued, are easier to install. And less wires equals less weight. WAIC also promotes the ability to reconfigure systems for upgrades or during integration for new product features.

“Wireless sensing is a recent development in the sensor world and TE is staying close to the leading edge of this innovation by introducing several new wireless products to the market,” Smith said. “And while drone and aircraft engineers have begun to evaluate wireless sensing technologies, drones and manned aircraft involve highly engineered ecosystems, so wireless sensor implementation will take some time. The market is not there quite yet.”

“However,” he continued, “wireless sensors will provide a weight reduction advantage in future generations of aircraft, a primary goal for new designs.”