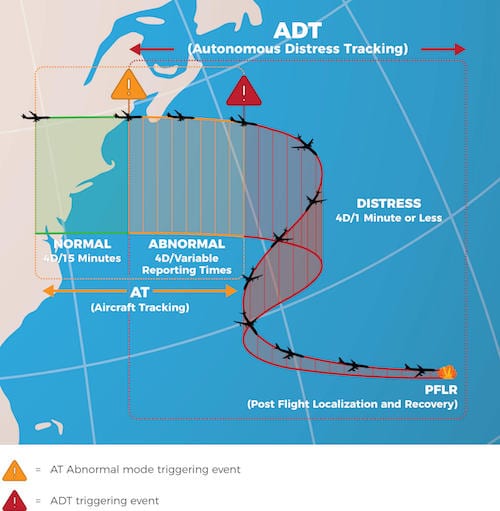

ICAO’s January 2021 timeline for the autonomous distress tracking portion of its GADSS initiative has been delayed until 2023. Pictured here is a visual representation of three aircraft reporting states: normal aircraft tracking, autonomous abnormal aircraft tracking and autonomous distress aircraft tracking.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has delayed its January 2021 date for its Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System (GADSS) initiative until 2023.

Under the newly implemented two-year postponement, the standard for the distress tracking element of GADSS will now be applicable as of January 2023 for new-build aircraft. Following a survey by ICAO on preparedness, the agency’s Air Navigation Commission recommended this postponement to 2023, which was approved by the ICAO Council this year.

Initially, the second phase of the Autonomous Distress Tracking (ADT) mandate was berthed as part of its GADSS initiative.

Triggered by the disappearance of the Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370, it was to occur on or after January 21, 2021. To comply with the mandate, aircraft with a maximum take-off weight over 27,000 kg (60,000 lbs) with an airworthiness certificate issued would have to autonomously transmit position information once every minute or less when an aircraft is in distress.

However, this 2021 date has been pushed back.

Perry Flint, head of USA corporate communications for the Montreal, Canada-based International Air Transport Association (IATA), said based on a recent survey, no IATA member state has enacted specific regulations on the distress tracking element of GADSS, although many have on the flight tracking element, for which standards are presently in force.

“The mandate for flight tracking is in force and airlines are complying. As for distress tracking, the industry should be ready to comply by the 2023 applicability date,” Flint said.

While the GADSS 15-minute, normal tracking standard is now being adhered to globally, many countries still haven’t set out their national regulations in support of its 1-minute standard for distress operations. Indeed, very few operators are complying with ICAO Annex 6 – 6.18 and Appendix 9 recommendations, as they see this as a forward-fit requirement only. Very few aviation authorities have adopted this into regulation yet.

“Airlines and manufacturers need to have those national regulations in place before they can know with full certainty what they need to adjust for in terms of onboard systems, and in light of this we’ve had to provide all concerned with the extra equipage time the Council agreed to earlier in March 2020,” said Anthony Philbin, chief of communications at ICAO.

According to Jon Gilbert, founder of San Diego-based Blue Sky Network, it was the European Aviation Safety Association (EASA) that started to take the lead to refine the original mandate on distress based on feedback from major airplane manufacturers.

“Airbus and Boeing had been very resistant to the [original] deadline because they felt they couldn’t modify their line production to incorporate this sort of off-the-line solution,” Gilbert said. “They said they needed two-to-three years to do this. Between Boeing and Airbus, there was uniform push to move the deadline. [Also,] EASA is an independent authority that covers 32 countries, mostly in the European Union. There was enough pressure around the world to re-evaluate the deadline and that’s what happened.”

According to Guillaume Aigoin, senior flight data expert at EASA, the European Union rules for air operations contain two requirements related and similar to ICAO GADSS: CAT.GEN.MPA.205 (the tracking mandate) and CAT.GEN.MPA.210 (the distress mandate). EASA has published Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM) for CAT.GEN.MPA.205. Furthermore, EASA published draft guidance material to support the implementation of CAT.GEN.MPA.210.

“All aircraft types in the scope of CAT.GEN.MPA.205 are capable of meeting this requirement, but so far, EASA has not approved any aircraft type that would permit the operator to comply with CAT.GEN.MPA.210,” Aigoin said.

EASA’s published Notice of Proposed Amendment NPA 2020-03 considers aspects not addressed by the ICAO GADSS ConOPS. To summarize, two of these differences include:

- A 6 NM accuracy for the location of the accident site: 200 meters as well as the transmission of a homing signal for 48 hours.

- The tracking of degraded conditions present before the impact. For example, unusual pitch and roll attitudes in the case of a loss of control, adverse climatic conditions after an explosive decompression or high vibrations following an engine failure.

One of the reasons for this postponement was development, testing, and certification schedules were very tight and required extraordinary efforts to meet the original 2021 goal with existing industry solutions. There were concerns that the technology could not accurately determine the location of where the flight stopped after an incident with severe damage to the aircraft to provide satisfactory compliance with this requirement.

Airlines can accept OEM specific solutions — most OEMs are considering ELT-DT (Distress Tracking ELTs) which notify the search and rescue in the event of a distress — or they choose a lower-cost option and retrofit their aircraft after their new purchase. The advantage here is they can install this on all their aircraft both forward-fit and retro-fit and have fleet commonality, and be able to receive the position reports directly to their OCC. Below are new GADSS tracking solutions to facilitate the tracking mandate and ease the 2023 transition.

Editorial Note: This is an excerpt of an article from our recently published April/May 2020 digital edition. Read the full article by signing up for a free email subscription to our bi-monthly digital edition.