New studies completed separately by Airbus, Boeing, and Embraer used live testing and digital modeling of aircraft cabin airflow to show how low the risk of transmitting COVID-19 in an aircraft cabin actually is. (Airbus)

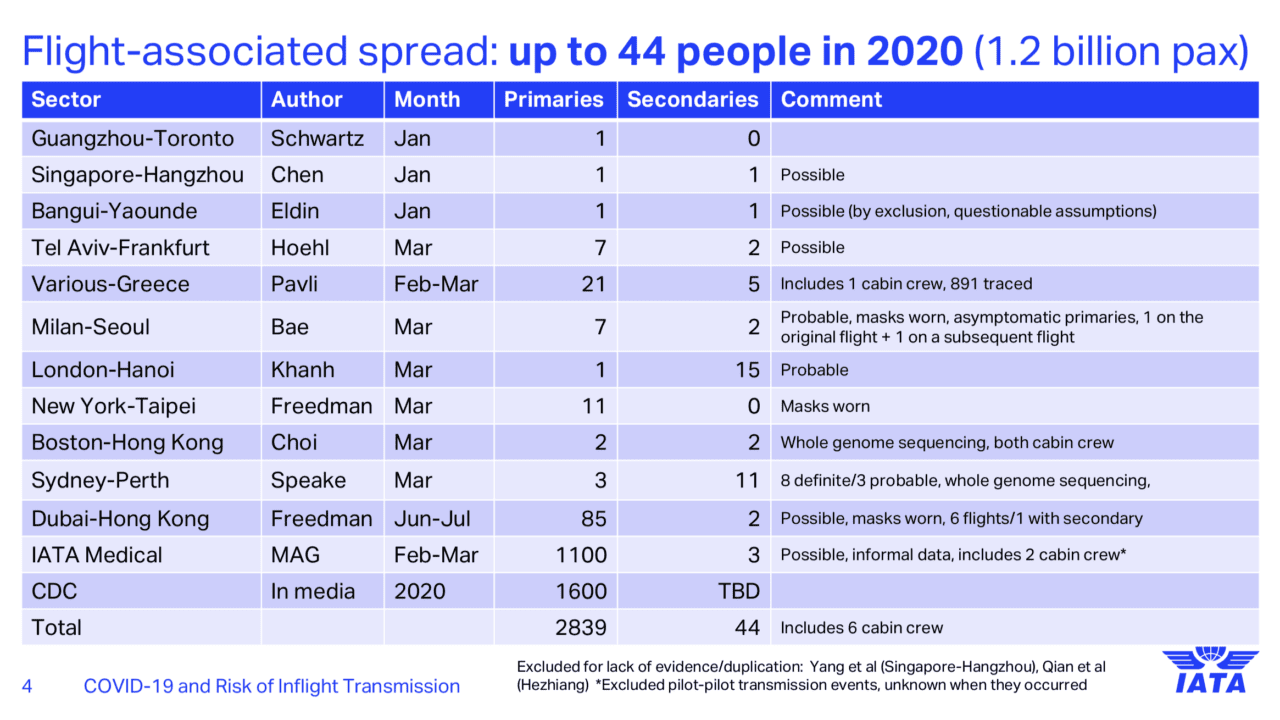

Among the 1.2 billion passengers that have traveled with commercial airlines since the beginning of 2020, there have been 44 cases of COVID-19 reported where transmission occurred in-flight, new data published by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) has found.

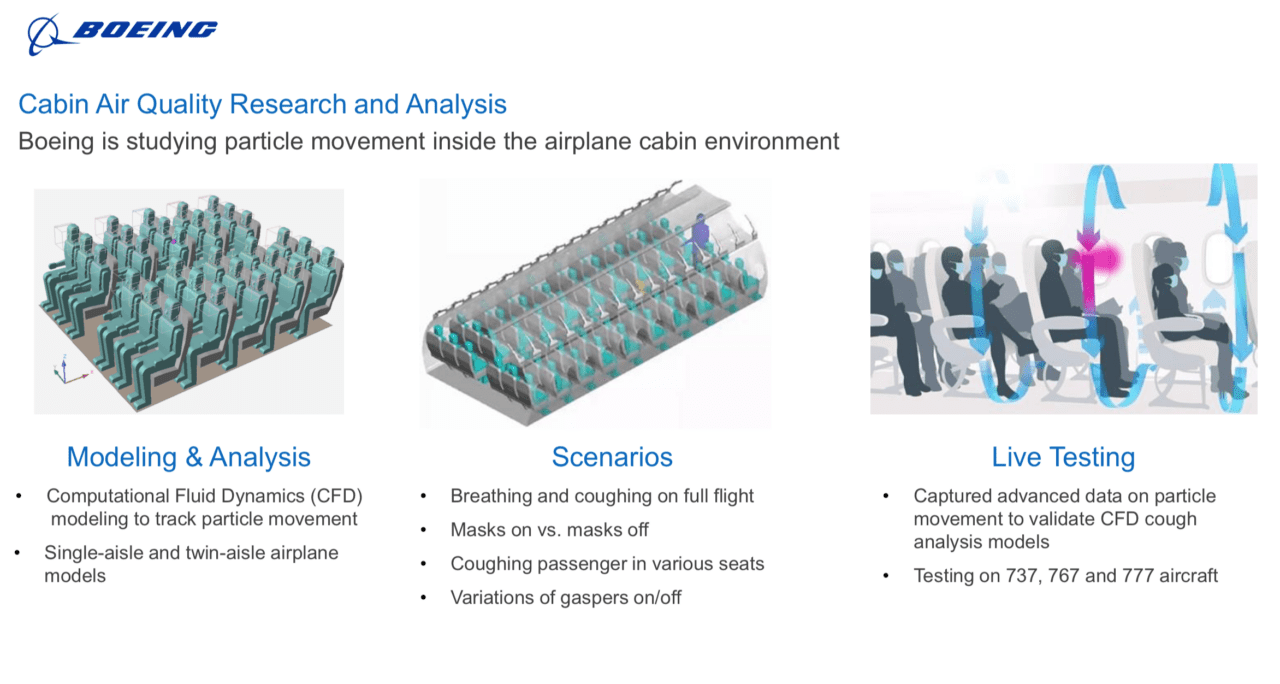

Data collected by IATA was released during a media briefing Thursday, Oct. 8 alongside presentations given by engineering leadership at Airbus, Boeing, and Embraer. Through the use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and real-live testing of passengers coughing in cabins and even airborne human safe viruses, the three companies released the most in-depth data and research on the risk of transmitting the COVID-19 coronavirus in-flight to date.

“The risk of a passenger contracting COVID-19 while onboard appears very low. With only 44 identified potential cases of flight-related transmission among 1.2 billion travelers, that’s one case for every 27 million travelers,” Dr. David Powell, IATA’s medical advisor said during the briefing. “We recognize that this may be an underestimate but even if 90 percent of the cases were unreported, it would be one case for every 2.7 million travelers. We think these figures are extremely reassuring. Furthermore, the vast majority of published cases occurred before the wearing of face coverings inflight became widespread.”

IATA collected the number of times a passenger was thought to have transmitted COVID-19 while in-flight, based on reported data since the beginning of 2020. (IATA)

The industry’s three largest commercial aircraft manufacturers used CFD to model how passengers wearing masks or not wearing them, breathing, coughing and talking can spread molecules through an aircraft cabin while in-flight. While all three used separate assumptions, methodologies, and criteria, they all came to a similar conclusion establishing credible evidence for the low risk an airline passenger faces on an average flight.

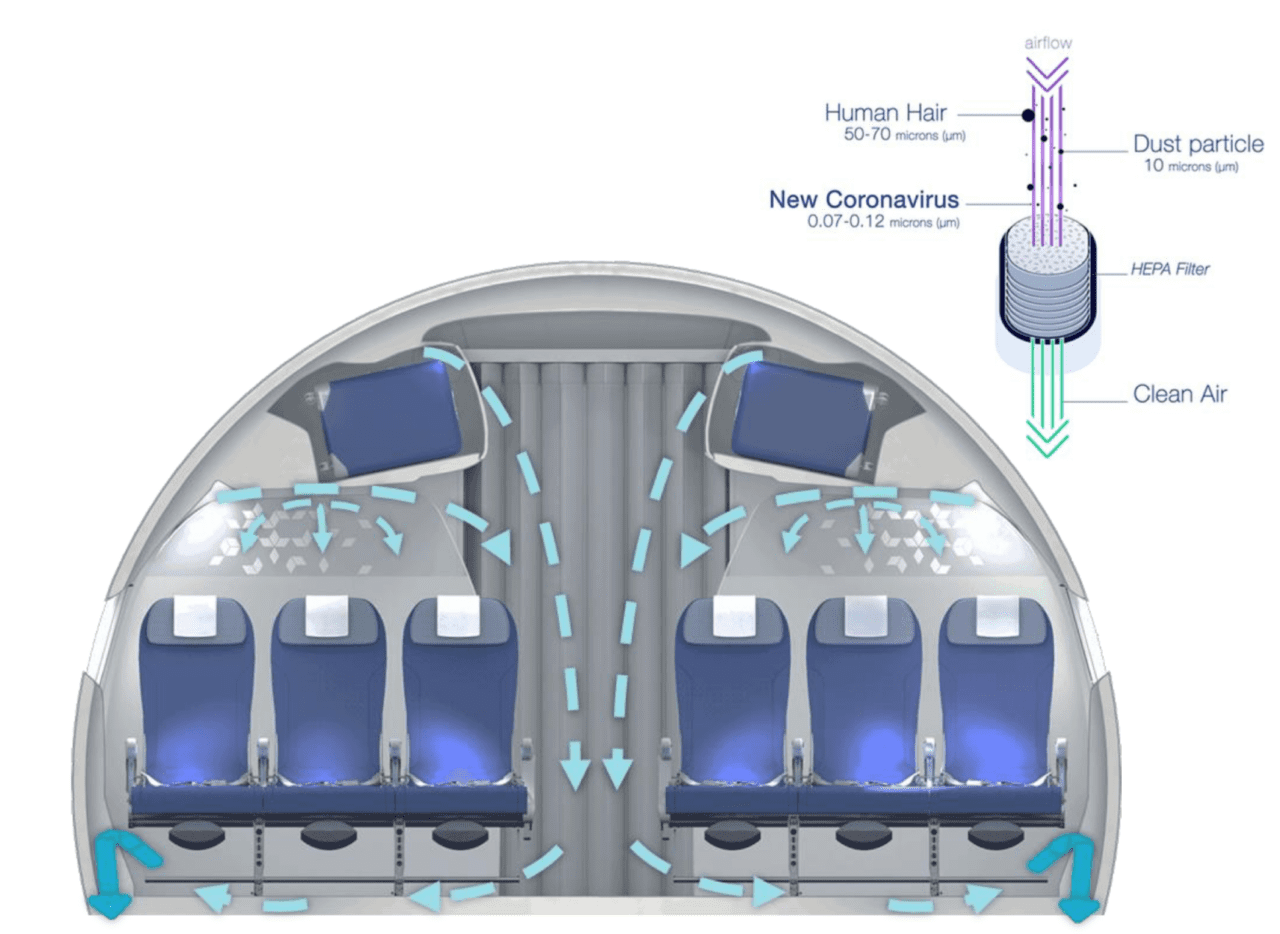

Although airlines and manufacturers continue to promote the effectiveness of High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters, the downward flow of air and high rates of air exchange that occur in cabins, passengers still express concerns over the ability of airlines to keep cabin environments safe from the risk of COVID-19 transitions. A survey of passengers that traveled during the month of June showed that 50 percent of passengers believe cabin air is as clean as a hospital, while another 50 percent say that they perceive cabin air as being dangerous.

All segments of the commercial air transportation industry have been trying to demonstrate that aircraft cabin environments are safer in some ways than the office buildings, bars, and restaurants that travelers frequent in their everyday lives.

Bruno Fargeon, former head of modeling, simulation, and engineering who took over as the project lead for the Airbus “Keep Trust in Air Travel” initiative said the Toulouse-based manufacturer used CFD to collect 50 million data points about how virus-sized microns and particles can flow through an aircraft cabin, including the airspeed, direction and temperature for each of the data points collected at “1,000 times per second.”

Airbus shows how airflow in a cabin helps to eliminate the spread of molecules transmitted in an aircraft cabin. (Airbus)

When asked how social distancing can be achieved in the aircraft cabin and whether airlines should eliminate the middle seat, Fargeon said the airflow and HEPA filters combined with mask-wearing can eliminate most of the risk associated with in-flight transmission of COVID-19.

“The social distance onboard the aircraft cannot be measured by taking a six-foot measurement. The social distance onboard the aircraft is ensured by the airflow washing away particles and droplets, and clearly, that’s the best protection that you can get today on board an aircraft,” Fargeon said. “The recommendations that are given today in bars and restaurants are places where the ventilation cannot be compared to the degree that you can find into an aircraft. That’s what makes the big difference between an aircraft environment and a classic ground environment.”

CFD modeling also allowed Fargeon’s engineering team to study scenarios where an A320 full of passengers are all wearing masks, some are wearing masks and others are wearing them incorrectly. His team also considered how leakages in cloth masks could allow molecules to escape, while still reaching the conclusion that the top-down airflow and air recirculation system is enough to counter the leakage.

Airbus also has studied some of the proposals of third party suppliers considering the use of curtains or physical plexiglass barriers between seats, finding that they could present more hazards than benefits.

“We do not recommend to use them. Either they’re very small and are not going to protect or they’re large and if they’re large they will distract the flow and disrupt the flow,” Fargeon said.

“They also pose extra challenges, they need to be cleaned, and properly cleaned, and also in aircraft, there are still some emergency recommendations and procedures that we have to respect. With these kind of devices, they also pose some other safety problems in terms of evacuation, they could also pose some other safety problems in terms of fire propagation into the aircraft, so all in all the benefit that it would bring is zero,” he added.

IATA’s data collection and the results of the cabin simulations align with the low numbers of reported in-flight reported in a peer-reviewed study by Freedman and Wilder-Smith in the Journal of Travel Medicine. That study also points to the extra layer of protection provided by passengers wearing masks as well.

All three companies admitted that there is still some risk involved with the possibility of transmitting the virus in-flight. HEPA filters, airflow, and mask-wearing still leave the possibility of a small number of particles emitted by one passenger who could have COVID-19 and not know it still reaching another passenger also seated in the cabin. But they believe that the education they’re providing to passengers and being as transparent as possible about how virus-sized microns flow through a cabin while in-flight shows how the low the risk actually is.

None of the live testing performed by Airbus, Boeing, and Embraer involved the actual simulation of a person who has COVID-19 coughing or breathing openly in-flight. Instead, they used smoke and other methods of studying how microns and molecules are eliminated by the airflow and recirculation that already occurs in cabins today.

Boeing provided an overview of how it is studying molecule movement through an aircraft cabin. (Boeing)

“We’ve actually done testing using MS-2 which is a live virus that is human safe,” said Dan Freeman, the chief engineer for Boeing’s Confident Travel Initiative. “We’ve done a whole variety of things, we’ve done testing with virus-sized particles, we’ve done testing with human safe viruses, in order to make sure that we completely understand the environment.”

Freeman said that Boeing’s analysis also showed that when a cough occurs in a single-aisle aircraft like the 737, their computational simulations and live testing showed that all of the measurable cough particles are eliminated about 90 seconds after the cough occurs. Boeing also found that larger droplets emitted by a person’s cough will drop out of the air faster because they’re heavier, while the “aerosol sized molecules” are the hardest to track and eliminate through airflow alone.

Embraer Senior Vice President of Engineer, Technology, and Strategy Luis Carlos Affonso said that the Brazilian manufacturer saw similar results to the studies performed by Airbus and Boeing. Their CFD and live testing also showed the difference between the risk of molecules generated by a cough reaching the breathing zone of other passengers is about 0.13 percent without a mask and 0.02 percent while wearing one.

“The human need to travel, to connect, and to see our loved ones has not disappeared. In fact, at times like this, we need our families and friends even more,” Affonso said. “Our message today is that because of the technology and procedures in place, you can fly safely – all the research demonstrates this. In fact, the cabin of a commercial aircraft is one of the safer spaces available anywhere during this pandemic.”